Claude-André Faucher-Giguère

Professor in the Department of Physics & Astronomy

First model to show how gas flows across universe into a supermassive black hole’s center

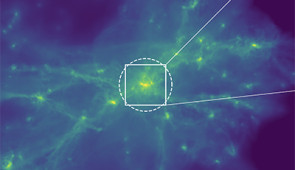

EVANSTON, Ill. — Galaxies’ spiral arms are responsible for scooping up gas to feed to their central supermassive black holes, according to a new high-powered simulation.

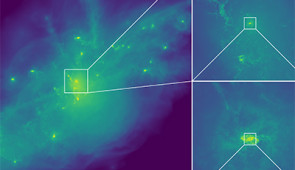

Started at Northwestern University, the simulation is the first to show, in great detail, how gas flows across the universe all the way down to the center of a supermassive black hole. While other simulations have modeled black hole growth, this is the first single computer simulation powerful enough to comprehensively account for the numerous forces and factors that play into the evolution of supermassive black holes.

The simulation also gives rare insight into the mysterious nature of quasars, which are incredibly luminous, fast-growing black holes. Some of the brightest objects in the universe, quasars often even outshine entire galaxies.

“The light we observe from distant quasars is powered as gas falls into supermassive black holes and gets heated up in the process,” said Northwestern’s Claude-André Faucher-Giguère, one of the study’s senior authors. “Our simulations show that galaxy structures, such as spiral arms, use gravitational forces to ‘put the brakes on’ gas that would otherwise orbit galaxy centers forever. This breaking mechanism enables the gas to instead fall into black holes and the gravitational brakes, or torques, are strong enough to explain the quasars that we observe.”

The research was published today (Aug. 17) in the Astrophysical Journal.

Faucher-Giguère is an associate professor of physics and astronomy at Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and a member of the Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA). Daniel Anglés-Alcázar, an assistant professor at the University of Connecticut and former CIERA fellow in Faucher-Giguère’s group, is the paper’s first author.

Equivalent to the mass of millions or even billions of suns, supermassive black holes can swallow 10 times the mass of a sun in just one year. But while some supermassive black holes enjoy a continuous supply of food, others go dormant for millions of years, only to reawaken abruptly with a serendipitous influx of gas. The details about how gas flows across the universe to feed supermassive black holes have remained a long-standing question.

To address this mystery, the research team developed the new simulation, which incorporates many of the key physical processes — including the expansion of the universe and the galactic environment on large scales, gravity gas hydrodynamics and feedback from massive stars — into one model.

“Powerful events such as supernovae inject a lot of energy into the surrounding medium, and this influences how the galaxy evolves,” Anglés-Alcázar said. “So we need to incorporate all of these details and physical processes to capture an accurate picture.”

Building on previous work from the FIRE ("Feedback In Realistic Environments") project, the new technology greatly increases model resolution and allows for following the gas as it flows across the galaxy with more than 1,000 times better resolution than previously possible.

“Other models can tell you a lot of details about what’s happening very close to the black hole, but they don’t contain information about what the rest of the galaxy is doing or even less about what the environment around the galaxy is doing,” Anglés-Alcázar said. “It turns out, it is very important to connect all these processes at the same time.”

“The very existence of supermassive black holes is quite amazing, yet there is no consensus on how they formed,” Faucher-Giguère said. “The reason supermassive black holes are so difficult to explain is that forming them requires cramming a huge amount of matter into a tiny space. How does the universe manage to do that? Until now, theorists developed explanations relying on patching together different ideas for how matter in galaxies gets crammed into the innermost one millionth of a galaxy’s size.”

With the new simulations, researchers can finally model how this happens. For example, the new simulation will help researchers understand the origin of the supermassive black hole at the center of our own Milky Way galaxy as well as the supermassive black hole at the center of the Messier 87 galaxy, which was famously captured by the Event Horizon Telescope in 2019. Next, the researchers aim to study large statistical populations of galaxies and their central black holes to better understand how black holes can form and grow under various conditions.

The study, “Cosmological simulations of quasar fueling to sub-parsec scales using Lagrangian hyper-refinement,” was supported by the Simons Foundation, the National Science Foundation and NASA.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/0ai1Si8Lg40" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Please credit all images to Anglés-Alcázar et al. 2021, ApJ, 917, 53.

Professor in the Department of Physics & Astronomy