Real-time dialogue with a dreaming person is possible

Dreamers were able to solve simple math problems and answer yes-or-no questions

- Link to: Northwestern Now Story

- Independent labs in France, Germany, Netherlands and U.S. collaborated on study

- Footage of experiment captured for a NOVA | PBS short film debuts today

- Northwestern researchers also developed a smartphone app for lucid dreaming

EVANSTON, Ill. --- Dreams take us to an alternative reality. They also happen while we're fast asleep. So, you might not expect that a person in the midst of a vivid dream would be able to perceive incoming questions and provide answers to them. But a new study led by Northwestern University researchers shows that, in fact, they can.

“Real-time dialogue between experimenters and dreamers during REM sleep” published today (Feb. 18) in the journal Current Biology. Read the study here.

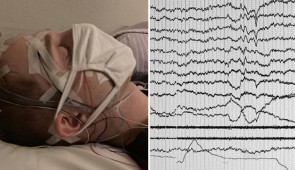

The researchers studied individuals who aimed to have a lucid dream, in which a person is aware they're dreaming. Study participants were briefed in bidirectional communication before sleep. Some also practiced with sensory stimulation, such as beeps or lights. Participants were instructed to signal researchers when they experienced a lucid dream, usually with a sequence of large eye movements to the left and to the right.

REM refers to the rapid eye movement phase of sleep in which lucid dreaming can occur. The researchers used polysomnographic data to confirm that study participants had reached the REM stage of sleep.

“We found that individuals in REM sleep can interact with an experimenter and engage in real-time communication,” said senior author Ken Paller, professor of psychology and director of the Cognitive Neuroscience Program in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences at Northwestern. “We also showed that dreamers are capable of comprehending questions, engaging in working-memory operations, and producing answers.

“Most people might predict that this would not be possible — that people would either wake up when asked a question or fail to answer, and certainly not comprehend a question without misconstruing it.”

While dreams are a common experience, scientists still haven’t adequately explained them. Relying on a person's recounting of dreams is also fraught with distortions and forgotten details. So Paller and colleagues decided to attempt communication with people during lucid dreams.

“Our experimental goal is akin to finding a way to talk with an astronaut who is on another world, but in this case, the world is entirely fabricated on the basis of memories stored in the brain," the researchers write. They realized finding a means to communicate could open the door in future investigations to learn more about dreams, memory, and how memory storage depends on sleep, the researchers say.

The paper is unique in that it includes four independently conducted experiments using different approaches to achieve a similar goal. In addition to the group at Northwestern in the U.S., studies were conducted at Sorbonne University in France; Osnabrück University in Germany; and Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands.

“We put the results together because we felt that the combination of results from four different labs using different approaches most convincingly attests to the reality of this phenomenon of two-way communication,” said Karen Konkoly, a Ph.D. student in psychology in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences at Northwestern and first author of the paper. “In this way, we see that different means can be used to communicate."

One of the individuals who readily succeeded with two-way communication had narcolepsy and frequent lucid dreams. Among the others, some had lots of experience in lucid dreaming and others did not. Overall, the researchers found that it was possible for people, while dreaming, to follow instructions, do simple math, answer yes-or-no questions, or tell the difference between different sensory stimuli. They could respond using eye movements or by contracting facial muscles. The researchers refer to these successful conversations as “interactive dreaming.” They chose questions with known answers so that they could assess whether participants’ answers were correct.

Konkoly says that future studies of dreaming could use these same methods to assess cognitive abilities during dreams versus wake. They also could help verify the accuracy of post-awakening dream reports. Outside of the laboratory, the methods could be used to help people in various ways, such as solving problems during sleep or offering nightmare sufferers novel ways to cope. Follow-up experiments run by members of the four research teams aim to learn more about connections between sleep and memory processing, and about how dreams may shed light on this memory processing.

Students in Paller's lab group have developed a smartphone app that aims to make it easier for people to achieve lucidity during their dreams. Information on the lucid app, and the link to download it, is available on Paller’s cognitive neuroscience lab site.

A documentary for PBS NOVA’s “What the Physics?!” series, captures a lucid dreaming experiment in Paller’s lab. “Dream Hackers: Bridge to Your Hidden Brain” was produced and directed by series host Greg Kestin, a theoretical physicist and education researcher at Harvard University. The program will debut online at 10 a.m. CST, Feb. 18 at WhatThePhysics.org/dream.

Funding credits

The Current Biology article was based upon work supported by the Mind Science Foundation, National Science Foundation grant BCS-1921678, Société Française de Recherche et Médecine du Sommeil (SFRMS), Hans-Mühlenhoff-Stiftung Osnabrück, a Vidi grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), and COST Action CA18106 supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).

The “What the Physics?!” documentary was supported by grant number FQXI-RFP-1822 from the Foundational Questions Institute and Fetzer Franklin Fund, a donor-advised fund of Silicon Valley Community Foundation.

Multimedia Downloads

Assets

CREDIT: K. Konkoly

CREDIT: K. Konkoly (animation by J. Stoughton)

CREDIT: C. Mazurek