A Northwestern University-led team of astronomers has captured the most detailed glimpse yet of a doomed star before it exploded.

Using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the international team identified a supernova’s source star, or progenitor, at mid-infrared wavelengths for the first time. These observations — combined with archival images from the Hubble Space Telescope — revealed the explosion came from a massive red supergiant star, cloaked in an unexpected shroud of dust.

The discovery may help solve the decades-old mystery of why massive red supergiants rarely explode. After all, theoretical models predict red supergiants should make up the majority of core-collapse supernovae. The new study shows these stars do explode but are simply hidden out of sight, within thick clouds of dust. With JWST’s new capabilities, astronomers can finally pierce through the dust to spot these phenomena, closing the gap between theory and observation.

The study was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. It marks the JWST’s first detection of a supernova progenitor.

“For multiple decades, we have been trying to determine exactly what the explosions of red supergiant stars look like,” said Northwestern’s Charlie Kilpatrick, who led the study. “Only now, with JWST, do we finally have the quality of data and infrared observations that allow us to say precisely the exact type of red supergiant that exploded and what its immediate environment looked like. We’ve been waiting for this to happen — for a supernova to explode in a galaxy that JWST had already observed. We combined Hubble and JWST data sets to completely characterize this star for the first time.”

An expert on the lives and deaths of massive stars, Kilpatrick is a research assistant professor at Northwestern’s Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics. Aswin Suresh, a graduate student in physics and astronomy at Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and member of Kilpatrick’s research group, is a key coauthor on the paper.

Reddest, dustiest progenitor ever observed

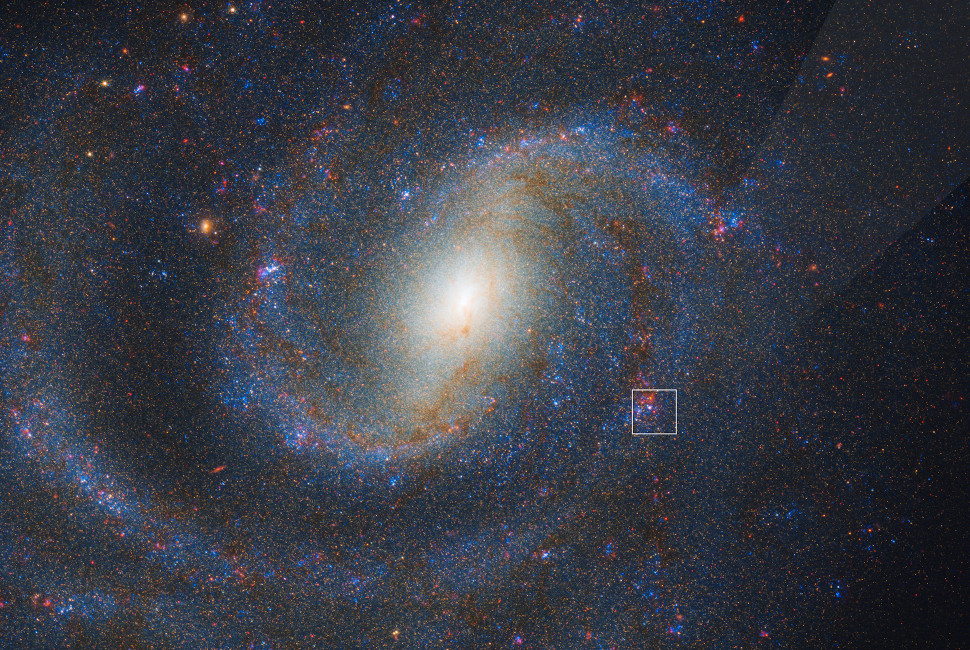

Using the All-Sky Automated Survey of Supernovae, astronomers first detected the supernova, dubbed SN2025pht, on June 29, 2025. Its light had traveled from a nearby galaxy called NGC 1637, located 40 million light-years away from Earth.

By comparing Hubble and JWST images of NGC 1637 from before and after the star’s explosion, Kilpatrick, Suresh and their collaborators found SN2025pht’s progenitor star. It was immediately striking — extremely bright and incredibly red. Although the star shined about 100,000 times brighter than our sun, surrounding dust obscured much of this light. The dusty veil was so thick, in fact, that the star appeared more than 100 times dimmer in visible light than it would appear without the dust. Because dust blocked out shorter, bluer wavelengths of light, the star also appeared surprisingly red.

“It’s the reddest, dustiest red supergiant that we’ve seen explode as a supernova,” Suresh said.

Massive stars in the late stages of their lives, red supergiants are among the largest stars in the universe. When their cores collapse, they explode as Type II supernovae, leaving behind either a neutron star or black hole. The most familiar example of a red supergiant is Betelguese, the bright reddish star in the shoulder of the constellation Orion.

“SN2025pht is surprising because it appeared much redder than almost any other red supergiant we’ve seen explode as a supernova,” Kilpatrick added. “That tells us that previous explosions might have been much more luminous than we thought because we didn’t have the same quality of infrared data that JWST can now provide.”

Clues hidden in dust

The deluge of dust could help explain why astronomers have struggled to find red supergiant progenitors. Most massive stars that explode as supernovae are the brightest and most luminous objects in the sky. So, theoretically, they should be easy to spot before they explode. But that hasn’t been the case.

Astronomers posit that the most massive aging stars also might be the dustiest. These thick cloaks of dust might dim the stars’ light to the point of utter undetectability. The new JWST observations support this hypothesis.

“I’ve been arguing in favor of that interpretation, but even I didn’t expect to see such an extreme example as SN2025pht,” Kilpatrick said. “It would explain why these more massive supergiants are missing because they tend to be dustier.”

In addition to the presence of dust itself, the dust’s composition was also surprising. While red supergiants tend to produce oxygen-rich, silicate dust, this star’s dust appeared rich with carbon. This suggests that powerful convection in the star’s final years may have dredged up carbon from deep inside, enriching its surface and altering the type of dust it produced.

“The infrared wavelengths of our observations overlap with an important silicate dust feature that’s characteristic of some red supergiant spectra,” Kilpatrick said. “This tells us that the wind was very rich in carbon and less rich in oxygen, which also was somewhat surprising for a red supergiant of this mass.”

A new era for exploding stars

The new study marks the first time astronomers have used JWST to directly identify a supernova progenitor star, opening the door to many more discoveries. By capturing light across the near- and mid-infrared spectrum, JWST can reveal hidden stars and provide missing pieces for how the most massive stars live and die.

The team now is searching for similar red supergiants that may explode as supernovae in the future. Observations by NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope may help this search. Roman will have the resolution, sensitivity and infrared wavelength coverage to see these stars and potentially witness their variability as they expel out large quantities of dust near the end of their lives.

“With the launch of JWST and upcoming Roman launch, this is an exciting time to study massive stars and supernova progenitors,” Kilpatrick said. “The quality of data and new findings we will make will exceed anything observed in the past 30 years.”

The study was supported by the National Science Foundation.