For 25 years, scientists at Northwestern Medicine have been studying individuals aged 80 and older — dubbed “SuperAgers” — to better understand what makes them tick.

These unique individuals, who show outstanding memory performance at a level consistent with individuals who are at least three decades younger, challenge the long-held belief that cognitive decline is an inevitable part of aging.

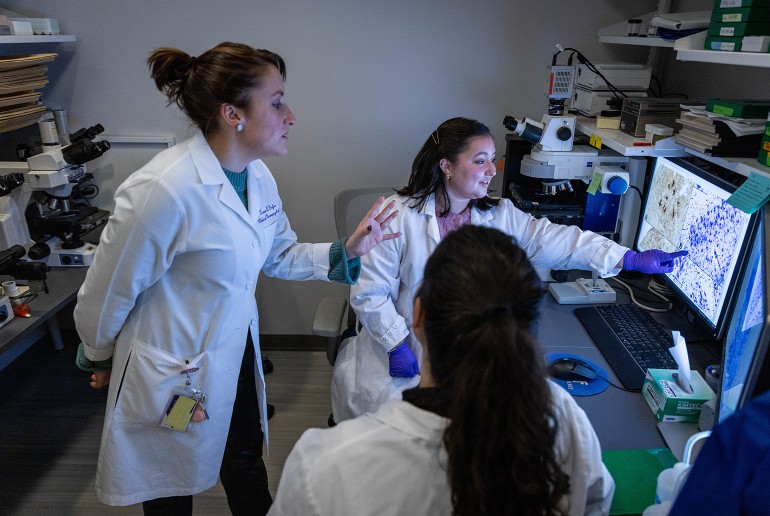

Over the quarter-century of research, the scientists have seen some notable lifestyle and personality differences between SuperAgers and those aging typically — such as being social and gregarious — but “it’s really what we’ve found in their brains that’s been so earth-shattering for us,” said Dr. Sandra Weintraub, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and neurology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

By identifying biological and behavioral traits associated with SuperAging, the scientists hope to uncover new strategies to promote cognitive resilience and delay or prevent Alzheimer’s and other diseases that cause cognitive decline and dementia.

- What we can learn from SuperAgers: Related story and video in Northwestern Magazine >

“Our findings show that exceptional memory in old age is not only possible but is linked to a distinct neurobiological profile. This opens the door to new interventions aimed at preserving brain health well into the later decades of life,” said Weintraub, corresponding author of a new paper summarizing the findings.

The paper will be published in a perspective piece in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association as part of the journal’s special issue commemorating the 40th anniversary of the National Institute on Aging’s Alzheimer’s Disease Centers Program and the 25th anniversary of the National Alzheimer Coordinating Center.

SuperAger brains are resilient, resistant

The term “SuperAger” was coined by Dr. M. Marsel Mesulam, who founded the Mesulam Institute for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer's Disease at Northwestern in the late 1990s.

Since 2000, a cohort of 290 SuperAger participants has passed through the Mesulam Center’s doors, and the scientists have autopsied 79 donated SuperAger brains. Some of the brains contained amyloid and tau proteins (also known as plaques and tangles), which are known to play key roles in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, but others didn’t develop any.

“What we realized is there are two mechanisms that lead someone to become a SuperAger,” Weintraub said. “One is resistance: they don’t make the plaques and tangles. Two is resilience: they make them, but they don’t do anything to their brains.”