Move over, gym rats. Bumblebees are now the true masters of macros.

In the first long-term, community-level field study of wild bumblebee nutrition, a team of ecologists led by Northwestern University and the Chicago Botanic Garden discovered that wild bees aren’t just flitting from flower to flower, collecting pollen at random. Instead, they are strategically targeting flowers that enable them to carefully balance their protein, fat and carbs.

Focusing on pollen consumption, the study revealed that coexisting bee species occupy two distinct nutrient niches. Larger bodied bees with longer tongues prefer pollen that’s high in protein but lower in sugars and fats. Bees with shorter tongues, however, tend to gather pollen that’s richer in carbs and fats. The scientists also found individual bees adjust their diets as their colonies grow and develop, reflecting changing nutritional needs throughout the season.

By dividing up nutritional resources, wild bumble bees can avoid competition, thrive together and keep their colonies buzzing strong all season long.

The study was published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

“Despite the general importance of wild pollinators, especially bees, we know very little about their nutritional needs,” said Northwestern’s Paul CaraDonna, the study’s senior author. “Given widespread pollinator declines that have been observed around the globe, this knowledge gap is surprising and concerning. Our research provides some of the best information yet on the availability of nutritional resources found in wildflowers and how pollinators use these resources. We can incorporate this work into our thinking about garden design, so we can select the right flowers that best support the nutritional needs of wild pollinators.”

An expert on plant-pollinator interactions, CaraDonna is an adjunct associate professor in the Program in Plant Biology and Conservation, a partnership between Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and the Chicago Botanic Garden. Justin Bain, a recent Ph.D. graduate from CaraDonna’s lab group, is the study’s first author. This work was a part of Bain’s dissertation.

In the dark about diet

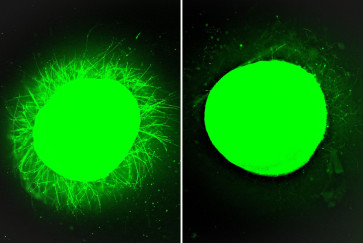

In the wild, bumblebees mainly consume two floral-based foods: sweet, syrupy nectar and fat- and protein-packed pollen. While adult bees sip nectar for a quick burst of energy, they also collect pollen for their babies, or larvae, to help them grow. Worker bees gather pollen from various flowers, pack it into special “baskets” on their hind legs and ferry it home to feed their young.

“We know that bees forage exclusively from flowers for pollen and nectar,” CaraDonna said. “Beyond that, we are in the dark. That is like humans shopping at a grocery store and assuming that all food items in the entire store have similar nutritional value. Clearly, that is a bad assumption.”

While other researchers have conducted short-term, lab-based studies on nutrition for single species of bees, the Northwestern and Chicago Botanic Garden team aimed to develop a more comprehensive nutritional map for how things play out in the wild. Instead of focusing on one bee species in isolation, the team examined a collection of bumblebee species in the wild to determine how species divide nutritional resources.

From steak to salad

To do this, the researchers observed eight different species of wild bumblebees at a field site in the Colorado Rockies. Across the span of eight years, the team meticulously tracked which flowers each bee species visited for pollen and then collected pollen samples from these plant species to understand their nutrient content.

The team took the pollen samples back into the lab, where they measured the macronutrient content of each pollen sample, specifically calculating the concentrations of protein, fat and carbohydrates. The full dataset included nutritional profiles for 35 different plant species.