Millions of people take metformin, a Type 2 diabetes medication that lowers blood sugar. The “wonder drug” has also been shown to slow cancer growth, improve COVID outcomes and reduce inflammation.

But until now, scientists have been unable to determine how, exactly, the drug works.

How it works

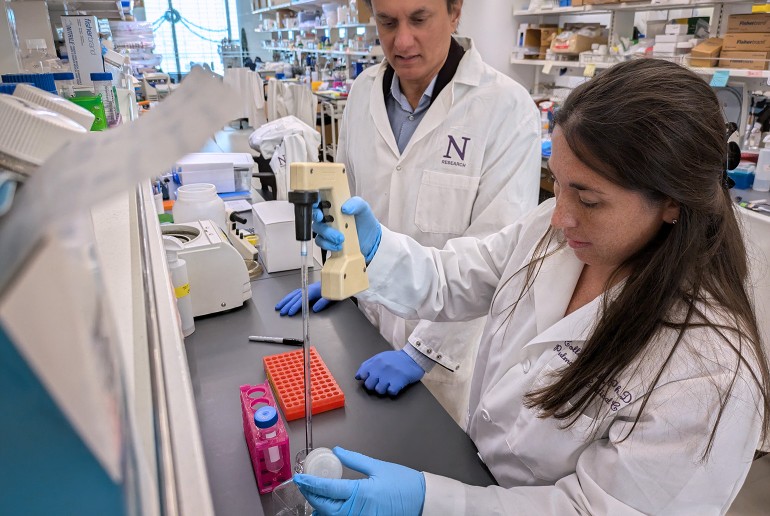

A new Northwestern Medicine study published in Science Advances has provided direct evidence in mice that the drug reversibly cuts the cell’s energy supply by interfering with mitochondria, often referred to as the cell’s “powerhouse,” to lower glucose levels.

More specifically, metformin blocks a specific part of the cell’s energy-making machinery called mitochondrial complex I. In doing so, the drug can target cells that may be contributing to disease progression without causing significant harm to normal, healthy cells.

“This research gives us a clearer understanding of how metformin works,” said corresponding author Navdeep Chandel, the David W. Cugell, MD, Professor of Medicine (Pulmonology and Critical Care), investigator with the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and a professor of biochemistry and molecular genetics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. The study’s first author is Colleen Reczek, research assistant professor of medicine (pulmonary and critical care medicine) at Feinberg.

“This research significantly advances our understanding of metformin’s mechanism of action,” Chandel said. “While millions of people take metformin, understanding its exact mechanism has been a mystery. This study helps explain that metformin lowers blood sugar by interfering with mitochondria in cells.”

Why it matters

Metformin has been used as a diabetes treatment for more than 60 years. The relatively inexpensive medication, which derives from compounds in the French lilac plant, is the first line of defense for many patients with Type 2 diabetes worldwide, Chandel said. In the U.S., some patients take it alongside other medications like new diabetes and weight-loss drugs — semaglutides such as Ozempic or Mounjaro.

Scientists have many theories about metformin’s effect on cells, but the theories are often grounded in research from distinct fields and have provided only indirect evidence to back hypotheses, Chandel said.

“Every year there's a new mechanism, a new target of metformin, and the next few years people debate those and don't come to a consensus,” said Chandel, who also is a member of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensives Cancer Center of Northwestern University.