In the 1840s, Frederick Douglass was already becoming famous as a leading abolitionist and orator, even giving speeches abroad. But legally, Douglass — who escaped from slavery in Maryland in 1838 — was still the property of a white man, Hugh Auld. He did not become legally free until Quaker activists helped purchase his freedom in 1846.

A new exhibition that opened June 6 at Northwestern’s Deering Library titled “Freedom for Everyone: Slavery and Abolition in 19th Century America,” will showcase documents that include rarely exhibited papers related to Douglass’s enslavement and later freedom, along with others that illuminate the experience of Black Americans in the 19th century which are housed in the Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections and University Archives and the Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies. A virtual version of the exhibition will also be available online.

Drawing from Black abolitionists

The title of the exhibition is drawn from an idea promoted by Black abolitionists and activists in the 19th century, who argued that the United States could not fully realize its founding ideals of liberty and equality until slavery was eliminated, according to Marquis Taylor, a Ph.D. student in the history department who curated the exhibition and helped process the collection.

“I wanted to center this idea that if Black people are free, then everyone is free,” Taylor said. The phrase “freedom for everyone,” he added, is a quote from Opal Lee. Known as “the grandmother of Juneteenth,” Lee is a Texas-based activist and educator who dedicated a lifetime to ensuring that Juneteenth would be recognized as a federal holiday.

Timed for Juneteenth

Her dream was realized last year, when President Biden signed a bill establishing the holiday. Now 95 years old, Lee was present at the signing. The opening of Northwestern’s exhibition has been timed to coincide with the celebration of Juneteenth, which commemorates June 19, 1865 — the day on which freedom was proclaimed for enslaved people in Texas, the last state of the Confederacy to fall to Union forces.

Since we have these documents that talk about slavery, the University’s first observance of the holiday felt like an opportunity to talk about this history in a really meaningful way.”

Achivist for the Black experience

“Since we have these documents that talk about slavery, the University’s first observance of the holiday felt like an opportunity to talk about this history in a really meaningful way,” said Charla Wilson, Northwestern’s archivist for the Black experience. Wilson and Taylor — along with library colleague Jill Waycie — processed the collections and redescribed the collection guides that the exhibition draws on together.

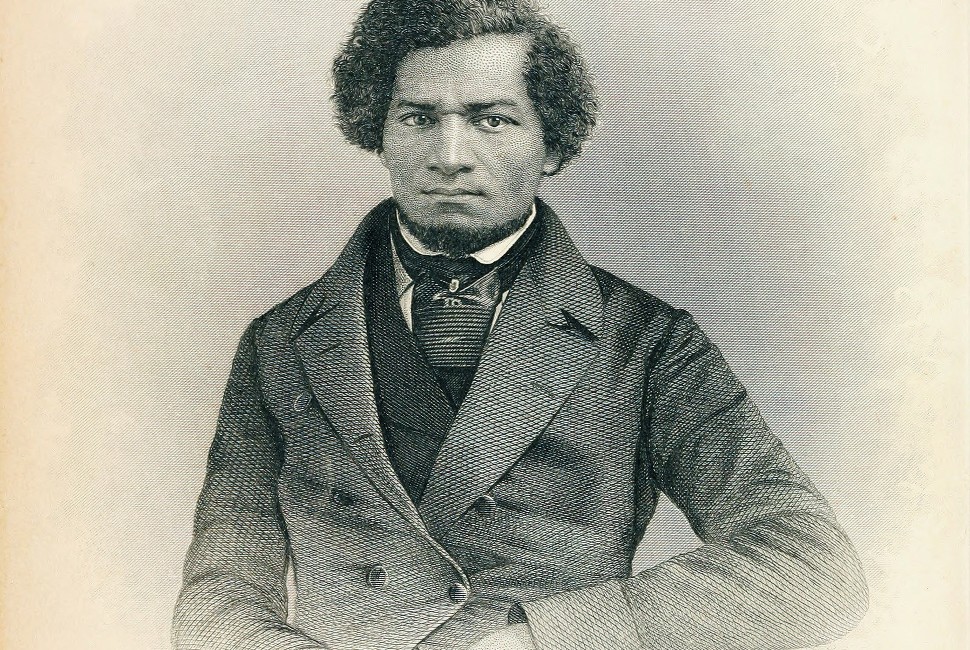

One of the exhibition’s centerpieces will be papers related to Frederick Douglass’s life as an enslaved person and free man. Douglass was a renowned abolitionist and one of the most-photographed people of the 19th century, according to Taylor, but the details of his experience while enslaved and journey to freedom remain unfamiliar to many people today.

Douglass spent his early life enslaved in Maryland. He escaped to Massachusetts via Pennsylvania and New York in 1838. The documents that will be on display include a bill of sale for Douglass from one of his enslavers to another, and manumission papers that resulted in his legal freedom in 1846, when English Quaker abolitionist Anna Richardson paid Douglass’s former enslaver Hugh Auld for his freedom while Douglass was still technically in a state of fugitivity.

Original letters and clippings

The Frederick Douglass Collection comprises 11 original letters and newspaper clippings, along with six copies (five of correspondence, and one receipt) from items held in other collections, notably the Gilder-Lehrman Institute of African American History in New York. The collection was donated to Northwestern by J.C. Shaffer, a newspaper publisher and businessman. Shaffer’s brother, W.H. Shaffer, had purchased some of the materials in the late 19th century directly from Douglass’s former enslaver.

Today, the papers offer a look at the legal reality of slavery as it was practiced in the early to mid-1800s, when transactions that involved human beings were common, and at the efforts of social reformers like Douglass and Richardson both before and after the Civil War. The number of enslaved people increased from under a million at the start of the 1800s to about four million by the time of the Civil War, according to Taylor, and the social debate about slavery escalated as the population of enslaved people grew.

“We wanted to tie this history to Juneteenth, and the abolition of slavery with the 13th Amendment, which proposed that those four million previously enslaved persons could now pursue the core tenets of this nation: liberty, equality and the pursuit of happiness,” Taylor said.

The exhibition is also one component of the library’s broader effort through the Decentering Whiteness initiative to bring the library’s collection up to date and improve accessibility for researchers while also removing problematic, non-inclusive language and terminology from collection finding aids, Wilson said.

After Juneteenth, original documents will all come out of the cases to protect them from environmental exposure during the summer months, and facsimiles will go in their place. During this time, the exhibit will remain open for visitors. The original documents will go back into the cases before students arrive in fall and will remain on view for most of fall quarter. After the exhibition closes, the materials will remain in Northwestern’s collection for use by researchers upon request.