Northwestern University scientists have developed the most advanced organoid model for human spinal cord injury to date.

In a new study, the research team used lab-grown human spinal cord organoids — miniature organs derived from stem cells — to model different types of spinal cord injuries and test a promising new regenerative therapy.

For the first time, the scientists demonstrated that human spinal cord organoids can accurately mimic the key effects of spinal cord injury, including cell death, inflammation and glial scarring, a dense mass of scar tissue that creates a physical and chemical barrier to nerve regeneration.

When treated with “dancing molecules” — a new therapy that reversed paralysis and repaired tissues in a previous animal study — the injured organoids showed significant outgrowth of neurites, the long extensions of neurons that connect the cells to one another. The glial scar-like tissues of treated injured organoids also significantly diminished. These results give researchers further hope that the treatment, which recently earned an Orphan Drug Designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), should improve outcomes for patients with spinal cord injuries.

The study was published today (Feb. 11) in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

“One of the most exciting aspects of organoids is that we can use them to test new therapies in human tissue," said Northwestern’s Samuel I. Stupp, the study’s senior author and inventor of dancing molecules. “Short of a clinical trial, it’s the only way you can achieve this objective. We decided to develop two different injury models in a human spinal cord organoid and test our therapy to see if the results resembled what we previously saw in the animal model. After applying our therapy, the glial scar faded significantly to become barely detectable, and we saw neurites growing, resembling the axon regeneration we saw in animals. This is validation that our therapy has a good chance of working in humans.”

A pioneer in self-assembling materials and regenerative medicine, Stupp is the Board of Trustees Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Chemistry, Medicine and Biomedical Engineering at Northwestern, where he has appointments in the McCormick School of Engineering, Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and Feinberg School of Medicine. He also directs the Center for Regenerative Nanomedicine (CRN). Nozomu Takata, a research assistant professor of medicine at Feinberg and member of CRN, is the paper’s first author.

Tiny organoid, giant advance

Grown in the lab from induced pluripotent stem cells, organoids are miniature, simplified versions of human organs. Although they are only partial organs, organoids mimic the tissue structure, cellular complexity and function of the real thing. This sophisticated mimicry makes organoids ideal for modeling human diseases, testing therapeutics and understanding organ development. Compared to testing treatments in animals and humans, testing in organoids is faster and much less expensive.

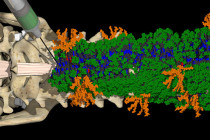

While other researchers have developed human organoids to investigate physiological aspects of the spinal cord, Stupp’s model represents a giant leap forward to find treatments for devastating, paralyzing human injuries. Measuring several millimeters in diameter, the organoids were large and mature enough to develop the injury model.

Stupp’s team grew the spinal cord organoids from stem cells over the course of months, allowing them to develop complex features including neurons and astrocytes. The team also was the first to add microglia — immune cells in the central nervous system — to simulate inflammatory responses to traumatic spinal cord injury.

“It’s kind of a pseudo-organ,” Stupp said. “We were the first to introduce microglia into a human spinal cord organoid, so that was a huge accomplishment. It means that our organoid has all the chemicals that the resident immune system produces in response to an injury. That makes it a more realistic, accurate model of spinal cord injury.”

What are ‘dancing molecules’?

After developing a mature spinal cord organoid, Stupp and his team wanted to examine the effects of injuries and subsequent treatment. First introduced in 2021, the dancing molecules therapy harnesses molecular motion to reverse paralysis and repair tissues after traumatic spinal cord injuries. It is part of the Stupp laboratory’s platform of supramolecular therapeutic peptides (STPs), technologies that use large assemblies of 100,000 or more molecules to activate cell receptors using the body’s own natural signals to regenerate and repair. (The concept of supramolecular therapies also is used in current GLP-1 drugs for weight loss and diabetes, an area that Stupp’s lab investigated nearly 15 years ago.)

Injected as a liquid, the dancing molecules therapy immediately gels into a complex network of nanofibers that mimic the extracellular matrix of the spinal cord. By fine-tuning the collective motion, or “dancing,” of the molecules within the nanofibers, Stupp’s team found the therapy connects more effectively with constantly moving cellular receptors.