Francesca Duncan

Corresponding author

Associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology (reproductive science in medicine) at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

New study in mice goes beyond fertility, also fixes hormone production and overall health

CHICAGO --- A woman’s ovaries are like a factory where eggs grow and produce hormones that regulate everything from menstruation and pregnancy to bone density and mood. As she and her factory age, production dwindles, and by the time she hits menopause (age 51, on average), the factory is preparing to shut its doors.

A new Northwestern Medicine study in mice has discovered a novel way to lengthen the “healthspan” of this factory — improving maintenance of the ovaries and preventing key age-related changes in ovarian function. “Healthspan” refers to the length of time a person remains healthy and free from serious illness or chronic diseases.

“The average age of menopause has stayed constant over the years, but women are living decades longer than that because of health and medical advances,” said corresponding author Francesca Duncan, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology (reproductive science in medicine) at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “We’ve changed the landscape of how we live, and our ovarian function needs to catch up so that we have an organ that functions proportionately to maintain women’s healthspans longer.”

The findings will be published Sept. 16 in the journal GeroScience.

For this study, researchers used Pirfenidone, which is commonly used to treat idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. But other ongoing studies are underway to identify optimal drug targets for ovarian fibrosis and to conduct clinical trials in women.

"This drug is not one that can be used in a clinical setting for this purpose because it has significant side effects, like liver toxicity, although we didn't see that in mice,” Duncan said. “However, we demonstrated proof-of-concept: we can modulate ovarian fibrosis and improve outcomes. We are now actively working to find a safe and effective drug to do this in humans.”

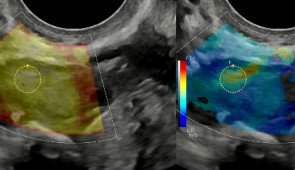

In a previous study, Duncan’s lab was the first to find that as ovaries age, they become excessively inflamed, fibrotic and stiff — similar to scarring in other tissues. Because cancer cells prefer collagen-rich, stiff environments, aged ovaries provide suitable conditions for cancer cells to proliferate, Duncan said.

Stiff ovaries also affect egg quality, the earlier study found, which could help explain why women’s fertility declines in their 30s and 40s.

In the new study, mice treated with medication to reduce ovarian scarring experienced higher follicle numbers, improved ovulation and maintained normal hormone levels.

“Right now, our solutions for the age-related decline in fertility, such as freezing one’s eggs, are a Band-Aid,” Duncan said. “You’re still going to be transferring those embryos into an older woman, which has its own risks.”

Lengthening a woman’s fertility window is only one part of the equation, Duncan said.

“We’re likely going to push the fertile window, but that is not the ultimate goal of the study,” Duncan said. “Not everyone is concerned about having children.”

This study focuses on ways to improve the ovarian environment, so it can continue producing critical hormones much later in a woman’s life. Decreased estrogen and progesterone levels accelerate bone loss, which increases the risk of osteoporosis. Low hormones also can lead to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease; can cause thinning of the vaginal walls, leading to discomfort during sex or urinary issues; and can lead to decreased cognitive function and mood.

“If you fix the ovarian environment, you solve all the problems because you have follicles and eggs that can contribute to fertility and hormone production,” Duncan said. “It’s fixing the root of the issue.”

The study is titled, “Systemic low‐dose anti‐fibrotic treatment attenuates ovarian aging in the mouse.” Funding for the study was provided by the Global Consortium for Reproductive Longevity and Equality.

Corresponding author

Associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology (reproductive science in medicine) at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.