Greenland’s thousands of peripheral glaciers have entered a new and widespread state of rapid retreat, a Northwestern University and University of Copenhagen study has found.

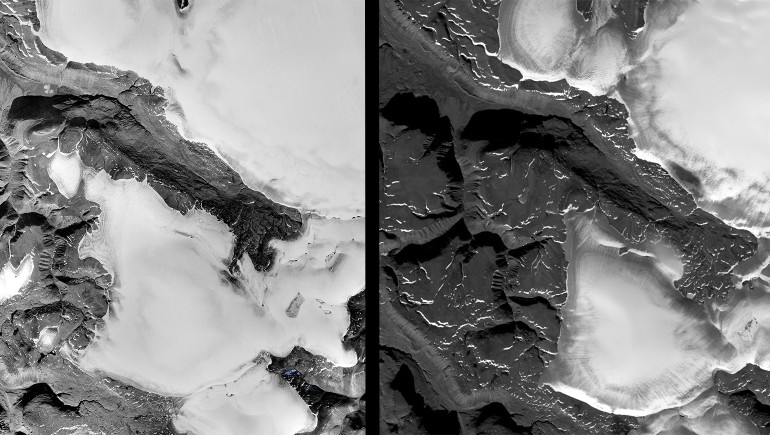

To piece together the magnitude of glacier retreat, the research team combined satellite images with historical aerial photographs of Greenland’s coastline, which is dotted with thousands of glaciers that are separate from the island’s massive central ice sheet. With these one-of-a-kind data, the researchers documented changes in the lengths of more than 1,000 of the country’s glaciers over the past 130 years.

Although glaciers in Greenland have experienced retreat throughout the last century, the rate of their retreat has rapidly accelerated over the last two decades. According to the multiyear collaborative effort between the United States and Denmark, the rate of glacial retreat during the 21st century is twice as fast as retreat during the 20th century. And, despite the range of climates and topographical characteristics across Greenland, the findings are ubiquitous, even among Earth’s northernmost glaciers.

The findings underscore the region’s sensitivity to rising temperatures due to human-caused climate change.

“Our study places the recent retreat of peripheral glaciers across Greenland’s diverse climate zones into a century-long perspective and suggests that their rate of retreat in the 21st century is largely unprecedented on a century timescale,” said Laura Larocca, the study’s first author. “The only major possible exception are glaciers in northeast Greenland, where it looks like recent increases in snowfall might be slowing retreat.”

The study finds that climate change explains the accelerated glacier retreat and that glaciers across Greenland respond quickly to changing temperatures. This highlights the importance of slowing global warming.

“Our activities over the next couple decades will greatly affect these glaciers. Every bit of temperature increase really matters,” Larocca said.

“This work is based on vast analyses of satellite imagery and digitization of thousands of historical aerial photographs — some taken during early mapping expeditions of Greenland from open-cockpit airplanes,” said Northwestern’s Yarrow Axford, a senior author on the study. “Those old photos extend the dataset back prior to the satellite era, when widespread observations of the cryosphere are rare. It’s quite extraordinary that we can now provide long-term records for hundreds of glaciers, finally giving us an opportunity to document Greenland-wide glacier response to climate change over more than a century.”

Axford is the William Deering Professor of Geological Sciences at Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. When the research began, Larocca was a Ph.D. candidate in Axford’s laboratory. Now, Larocca is a NOAA Climate & Global Change Postdoctoral Fellow hosted at Northern Arizona University. She will join Arizona State University’s School of Ocean Futures as an assistant professor in January 2024.

While climate change’s effects on Greenland are well studied, most researchers focus on the Greenland Ice Sheet, which covers roughly 80% of the country. But fluctuations in Greenland’s peripheral glaciers — the smaller ice masses distinct from the ice sheet that dot the country’s coastline — are widely undocumented, in part due to a lack of observational data.