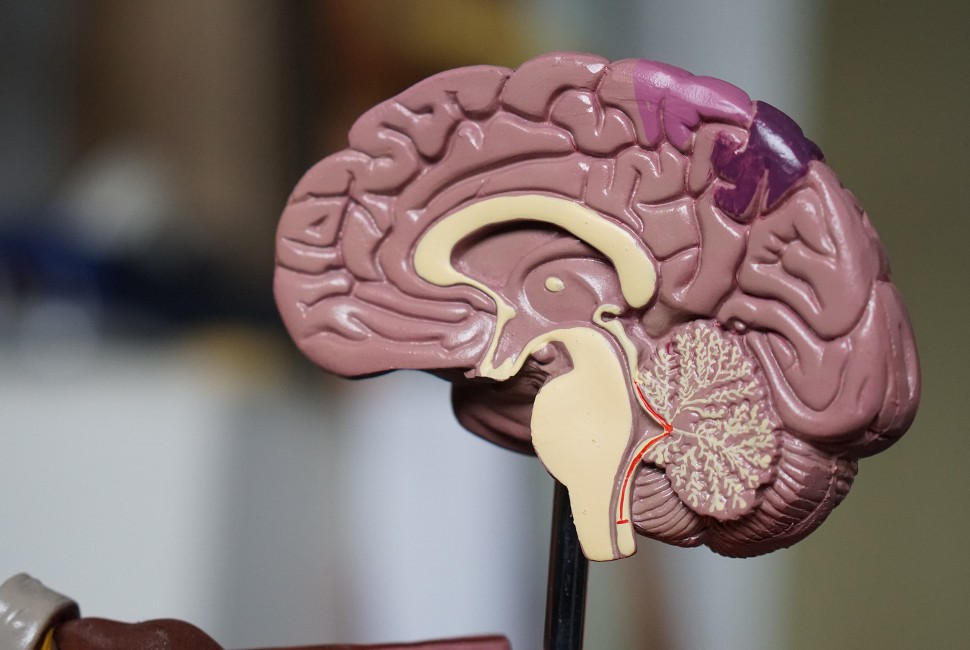

Every part of the brain surface (the cerebral cortex) has a specific job description. Some areas move the arms, others the legs, still others make it possible to see or speak.

But one part of the brain surface, a region called the temporal pole because it is at the very tip of the temporal lobe, could not be linked to a specific function for at least the first 100 years of research on the cortex.

Northwestern Medicine scientists have just discovered that this mysterious and seemingly silent surface is actually one of the most colorful regions of the brain. It has critical functions in word comprehension, face recognition and the regulation of behavior.

The paper was recently published in Annals of Neurology.

The scientists were able to identify this region’s previously unknown function through the investigation of 28 patients with a unique disease, known as TDP-C, that ultimately destroys the temporal pole. The cases reviewed post-mortem offer the most precise delineation of the brain areas that are first hit in a disease that progresses over 10 to 15 years.

“Research on this disease helps us understand how the brain decodes the meaning of words, the feelings of others and the identity of faces,” said study corresponding author Dr. Marsel Mesulam, chief of behavioral neurology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and a Northwestern Medicine neurologist. “This knowledge will help to determine the nature of the disease and the nature of brain networks that are responsible for word comprehension, person identification and the monitoring of interpersonal conduct.”

Now Northwestern researchers are studying the relationship between the temporal pole and these complex functions, and the nature of the relationships between TDP-C and the temporal pole.

“Answering these questions is key for helping patients with this condition,” said Mesulam, also the Ruth Dunbar Davee Professor of Neuroscience and founder of the Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease. “The next steps in the research are to identify the unique properties of the areas targeted by TDP-C, determine how the disease progresses and find out if there are patient-specific risk factors.”

The patients with TDP-C had been followed longitudinally at the Mesulam Center. The longitudinal data on brain function was linked to the tissue damage seen by examination with the microscope after autopsy.

Other Northwestern authors include Emily Rogalski, Tamar Gefen, Margaret Flanagan, Rudolph Castellani, Pouya Jamshidi, Elena Barbieri, Jaiashre Sridhar, Allegra Kawles, Sandra Weintraub and Changiz Geula.