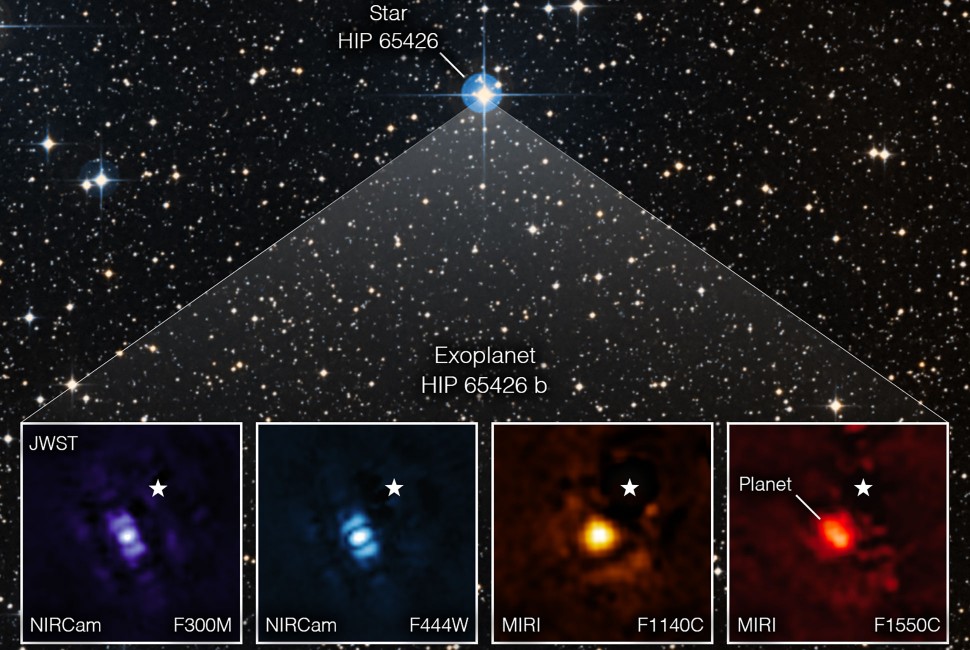

For the first time, a team of astronomers — including Northwestern University’s Jason Wang — used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to take a direct image of a planet outside our solar system. The exoplanet is a gas giant, meaning it has no rocky surface and could not be habitable.

The image, as seen through four different light filters, shows how Webb’s powerful infrared gaze can easily capture worlds beyond our solar system, pointing the way to future observations that will reveal more information than ever about exoplanets.

The exoplanet in Webb’s image, called HIP 65426 b, is about 6 to 12 times the mass of Jupiter, and these observations could help narrow that down even further. It is young as planets go — about 15 to 20 million years old, compared to our 4.5-billion-year-old Earth.

“It was so exciting to help produce the Webb’s first image of an exoplanet,” Wang said. “Exoplanets have never been directly imaged at some of these wavelengths before, so it has been an exciting and fun month figuring out how to analyze the data and reveal this faint planet hiding underneath the glare of its bright host star. The image quality was better than we expected, and I’m really excited about using Webb images like these to understand atmospheric physics and what these planets are made of. It was also really great to work together with experts from all around the world to make this image. We were all focused on imaging this exoplanet with Webb, and it’s a great feeling to see everything work.”

Wang is an assistant professor of physics and astronomy in Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and a member of the Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA). He was part of the Webb team that designed the data pipeline used to reveal the exoplanet hidden behind the glare of its host star.

“It was really great to work together with experts from all around the world to make this image. We were all focused on imaging this exoplanet with Webb, and it’s a great feeling to see everything work.”

– Astrophysicist Jason Wang

Astronomers discovered the planet in 2017 using the SPHERE instrument on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile and took images of it using short infrared wavelengths of light. The Webb image, taken in mid-infrared light, reveals new details that ground-based telescopes would not be able to detect because of the intrinsic infrared glow of Earth’s atmosphere.

Researchers have been analyzing the data from these observations and are preparing a paper they will submit to journals for peer review. But Webb's first capture of an exoplanet already hints at future possibilities for studying distant worlds.

Because HIP 65426 b is about 100 times farther from its host star than Earth is from the sun, it is sufficiently distant from the star that Webb can easily separate the planet from the star in the image.

“Obtaining this image felt like digging for space treasure,” said Aarynn Carter, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who led the analysis of the images. “At first all I could see was light from the star, but with careful image processing I was able to remove that light and uncover the planet.”

Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) are both equipped with coronagraphs, which are sets of tiny masks that block out starlight, enabling Webb to take direct images of certain exoplanets like this one. NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, slated to launch later this decade, will demonstrate an even more advanced coronagraph.

Taking direct images of exoplanets is challenging because stars are so much brighter than planets. The HIP 65426 b planet is more than 10,000 times fainter than its host star in the near-infrared, and a few thousand times fainter in the mid-infrared.