‘Oddball supernova’ appears strangely cool before exploding

Never-before-seen scenario ‘stretches what’s physically possible’

- Link to: Northwestern Now Story

- Without hydrogen, which conceals heat, stars that explode as supernovae should be blue and hot

- Astronomers find hydrogen-free supernova’s source star was abnormally cool and yellow

- Researchers believe the star might have shed its hydrogen layer in violent death throes before exploding

- Event adds to mounting evidence that stars can erupt, lose mass right before their final explosion

EVANSTON, Ill. — A curiously yellow star has caused astrophysicists to reevaluate what’s possible within our universe.

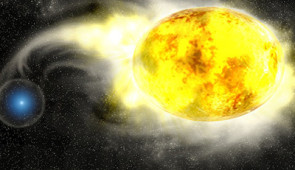

Led by Northwestern University, the international team used NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope to examine the massive star two-and-a-half years before it exploded into a supernova. At the end of their lives, cool, yellow stars are typically shrouded in hydrogen, which conceals the star’s hot, blue interior. But this yellow star, located 35 million lightyears from Earth in the Virgo galaxy cluster, was mysteriously lacking this crucial hydrogen layer at the time of its explosion.

“We haven’t seen this scenario before,” said Northwestern’s Charles Kilpatrick, who led the study. “If a star explodes without hydrogen, it should be extremely blue — really, really hot. It’s almost impossible for a star to be this cool without having hydrogen in its outer layer. We looked at every single stellar model that could explain a star like this, and every single model requires that the star had hydrogen, which, from its supernova, we know it did not. It stretches what’s physically possible.”

The team describes the peculiar star and its resulting supernova in a new study, which was published today (May 5) in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. In the paper, the researchers hypothesize that, in the years preceding its death, the star might have shed its hydrogen layer or lost it to a nearby companion star.

Kilpatrick is a postdoctoral fellow at Northwestern’s Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA) and member of the Young Supernova Experiment, which uses the Pan-STARSS telescope at Haleakalā, Hawaii, to catch supernovae right after they explode.

Catching a star before it explodes

After the Young Supernova Experiment spotted supernova 2019yvr in the relatively nearby spiral galaxy NGC 4666, the team used deep space images captured by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, which fortunately already observed this section of the sky.

“What massive stars do right before they explode is a big unsolved mystery,” Kilpatrick said. “It’s rare to see this kind of star right before it explodes into a supernova.”

The Hubble images showed the source of the supernova, a massive star imaged just a couple years before the explosion. Although the supernova itself appeared completely normal, its source — or progenitor star — was anything but.

“When it exploded, it seemed like a very normal hydrogen-free supernova,” Kilpatrick said. “There was nothing outstanding about this. But the progenitor star didn’t match what we know about this type of supernova.”

Direct evidence of violent death

Several months after the explosion, however, Kilpatrick and his team discovered a clue. As ejecta from the star’s final explosion traveled through its environment, it collided with a large mass of hydrogen. This led the team to hypothesize that the progenitor star might have expelled the hydrogen within a few years before its death.

“Astronomers have suspected that stars undergo violent eruptions or death throes in the years before we see supernovae,” Kilpatrick said. “This star’s discovery provides some of the most direct evidence ever found that stars experience catastrophic eruptions, which cause them to lose mass before an explosion. If the star was having these eruptions, then it likely expelled its hydrogen several decades before it exploded.”

In the new study, Kilpatrick’s team also presents another possibility: A less massive companion star might have stripped away hydrogen from the supernova’s progenitor star. The team, however, will not be able to search for the companion star until after the supernova’s brightness fades, which could take up to 10 years.

“Unlike it’s normal behavior right after it exploded, the hydrogen interaction revealed it’s kind of this oddball supernova,” Kilpatrick said. “But it’s exceptional that we were able to find its progenitor star in Hubble data. In four or five years, I think we will be able to learn more about what happened.”

The study, “A cool and inflated progenitor candidate for the type Ib supernova 2019 yvr at 2.6 years before explosion,” was supported by NASA (award numbers GO-15691 and AR-16136), the National Science Foundation (award numbers AST-1909796, AST-1944985), the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, the VILLUM Foundation and the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence. In addition to the Hubble Space Telescope, the researchers used instruments at the Gemini Observatory, Keck Observatory, Las Cumbres Observatory, Spitzer Space Telescope and the Swope Telescope.

Multimedia Downloads

Interview the Experts