Indoor dust is evolving — and not in a good way.

A new Northwestern University study is the first to find that bacteria living in household dust can spread antibiotic resistance genes. Although most bacteria are harmless, the researchers believe these genes could potentially spread to pathogens, making infections more difficult to treat.

“This evidence, in and of itself, doesn’t mean that antibiotic resistance is getting worse,” said Northwestern’s Erica Hartmann, who led the study. “It’s just one more risk factor. It’s one more thing that we need to be careful about.”

The study was published today (Jan. 23) in the journal PLOS Pathogens. Hartmann is an assistant professor of environmental engineering in Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering.

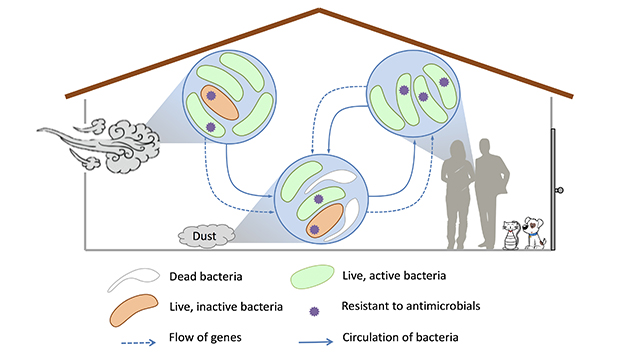

A bacterium can share its genes by using either of two methods: dividing, which is the equivalent to having a baby, or horizontal gene transfer. The primary method for spreading antibiotic resistance genes among species, horizontal gene transfer occurs when a bacterium makes a copy of its genes and swaps them with a neighbor.

Bacteria can share many different types of genes — as long as the genes have mobile segments of DNA. Hartmann and her team were the first to find that antibiotic resistance genes in dust microbes have mobile capabilities.

Microbes share genes when they get stressed out. They aren’t equipped to handle the stress, so they share genetic elements with a microbe that might be better equipped.”

environmental engineer

“We observed living bacteria have transferrable antibiotic resistance genes,” Hartmann said. “People thought this might be the case, but no one had actually shown that microbes in dust contain these transferrable genes.”

Although it is rare for pathogens to live in indoor dust, they can hitchhike into homes and mingle with existing bacteria.

“A nonpathogen can use horizontal gene transfer to give antibiotic resistance genes to a pathogen,” Hartmann explained. “Then the pathogen becomes antibiotic resistant.”

Why do bacteria share genes? Hartmann says they can’t handle the stress of being indoors. The indoor environment might be too dry and cold without enough food, for example, or it might be occasionally spritzed with antimicrobial solutions. (Hartmann, by the way, recommends dusting with a damp cloth instead of using antimicrobial solutions, which can make bacteria more resistant to antibiotics.)

“Microbes share genes when they get stressed out,” Hartmann said. “They aren’t equipped to handle the stress, so they share genetic elements with a microbe that might be better equipped.”

The study, “Mobilization antibiotic resistance genes are present in dust microbial communities,” was supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the Biology & the Built Environment Center at the University of Oregon.