Mayda Velasco’s energy level is admirable, especially for someone who just returned to blustery Chicago after a conference in the Caribbean. As one of the world’s top particle physicists, Velasco is constantly traveling across the globe, logging 100,000 miles or more every year. By now, when she books an international flight, she’s automatically upgraded.

“I live on a plane,” Velasco says, smiling through sips of an early morning Coke Zero.

Growing up in Puerto Rico, Velasco had her sights set on medicine. A stellar student all her life, Velasco had already aced the MCAT and was preparing for medical school when she earned an internship at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, or “Fermilab,” where she became fascinated with the field that turned out to be her true calling.

“I was exposed to particle physics beyond the courses you get in school, looking at real questions the field was trying to answer,” Velasco says. “I was hooked from that experience.”

Velasco dove deeper into these questions during graduate school at Northwestern, where she worked with professors Ralph Segel and the late Donald Miller to understand fundamental particles like electrons and quarks, which make up everything in the universe from people and mountains to planets and stars. Understanding these particles, which Velasco calls “the dinosaurs of the universe,” can provide important insights into big, unanswered questions like how and when the universe began – and if and when it will ever collapse.

After finishing her doctoral studies in Evanston, Velasco served as a fellow — and then a staff member —with the European Organization for Nuclear Research, or CERN, in Switzerland. She returned to Northwestern in 1999 as a professor in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Physics and Astronomy, where she won a Sloan Fellowship and a Woodrow Wilson Award.

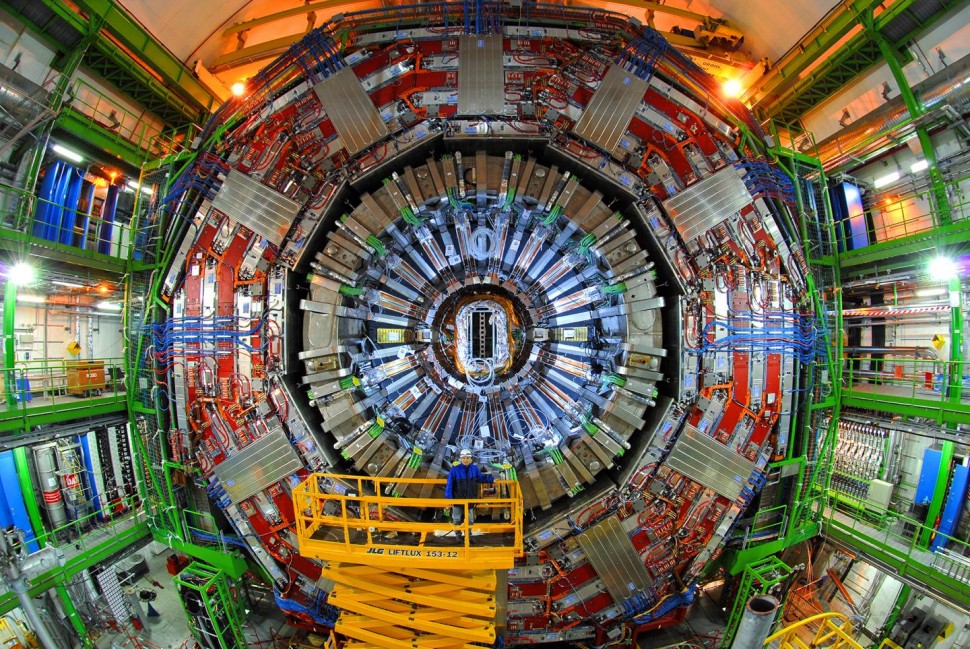

Velasco continues to work with CERN, now using the Large Hadron Collider to understand the recently discovered Higgs boson particle, which Velasco herself had a hand in identifying.

“At every step, I have changed topics within particle physics,” says Velasco, who is now looking at the interactions of fundamental particles, which she says is “very easy” to explain. To Velasco, this work may be simple, but to the average person, it’s astonishing, virtually incomprehensible: Sending tiny particles through an electric field that gets bent by a ring of magnets, and crashing the energy beams these fields create into each other at extremely high speeds — once every 25 nanoseconds.

“Let me show you,” Velasco says. “If you don’t mind me being a nerd.”

She pulls up an image of the Large Hadron Collider, which sits 100 meters underground at CERN. It looks like a huge human eye, with a ring of magnets resembling an iris and iridescent glass making a monster-sized cornea. Finding the technician in the image is like is like looking at an I Spy book; searching for a green marble in an overloaded junk drawer.

An island hub

In 2013, unexpected events spurred Velasco in yet another new direction. She was in Taiwan for a conference when her father called with news: Velasco’s mother, thousands of miles away in Puerto Rico, was ill. As her parents got older, Velasco had been receiving these calls more often, and she was usually overseas — Japan, Europe — unable to help directly. Determined to continue pathbreaking science and support her family simultaneously, Velasco created her own institute in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico.

As founder and director of the Colegio De Fisica Fundamental E Interdiciplinaria De Las Americas, or COFI, Velasco brings together particle theorists and computational and experimental experts from across the globe to discuss their work and identify opportunities for collaboration. Throughout the year, directors of other research entities — CERN, Argonne National Laboratory in the U.S., the Soltan Institute for Nuclear Studies in Poland, and The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Italy — converge on the Caribbean island alongside government officials and academic leaders from Northwestern and elsewhere to share key insights and new ways forward in the field of particle physics.

“Many experts in the field were already collaborating virtually, but that’s not enough,” Velasco says. “We need to have a critical mass of individuals come together to explore a project.”

In addition to retreats and seminars, COFI also offers fellowships for underrepresented groups and joint appointments with institutions like Fermilab and Northwestern. The opportunity to work with, and learn from, Velasco and other powerhouse scientists draws hundreds every year.

In recognition of COFI and her contributions to particle physics, Velasco was recently named the Chair on Fundamental and Interdisciplinary Physics at Northwestern University by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). One of only 19 people in the U.S. to receive this award since its establishment in 1992, Velasco says she almost missed the opportunity to be recognized.

“I got an email from the U.S. State Department saying that they wanted to talk to me, and I assumed they just wanted some advice,” Velasco says. “I even considered not connecting because I was too busy. But I figured it would be an opportunity to tell them about COFI, and when I called them they of course already knew all about it.”

Velasco (bottom left) visits COFI with students and fellow professors

Velasco (bottom left) visits COFI with students and fellow professors

Today, Velasco says she is just as dedicated to her work as ever, and happily so. She loves what she does, and now that she’s earned a reputation as a world-leading expert, Velasco is increasingly focused on supporting science in all forms and across the globe.

In March, Velasco traveled from Chicago to COFI to host “Women in Science and Technology,” a symposium coinciding with International Women’s Day. At the event, Velasco and others shared their research and their unique career trajectories.

“I spoke on a panel alongside a chemist, a geneticist, a computer scientist, an astronomer and others,” she says. “We filled every seat a week and a half before the registration deadline.”

Velasco is still devoted to research and teaching, and says this international community building is key to advancing her field and countless others.

“By reaching out to other experts, we all enrich our science.”