Weekly doses of glucocorticoid steroids, such as prednisone, help speed recovery in muscle injuries, reports a new Northwestern Medicine study. The weekly steroids also repaired muscles damaged by muscular dystrophy.

The studies were conducted in mice, with implications for humans.

One of the major problems of using steroids such as prednisone is they cause muscle wasting and weakness when taken long term. This is a significant problem for people who take steroids for many chronic conditions, and can often result in patients having to stop steroid treatments.

But the new study showed weekly doses — rather than daily ones — promote muscle repair.

“We don’t have human data yet, but these findings strongly suggest some alternative ways of giving a very commonly used drug in a manner that doesn’t harm, but in fact helps muscle,” said lead investigator Dr. Elizabeth McNally, the Elizabeth J. Ward Professor of Genetic Medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and a Northwestern Medicine physician.

McNally also is the director of the Center for Genetic Medicine at Feinberg.

The study was published online in May in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

In the study, normal mice with a muscle injury received steroids just before injury and for two weeks after the injury. Mice receiving two weekly doses of steroids after the injury performed better on treadmill testing and had stronger muscle than mice receiving a placebo.

Mice that received daily steroids for two weeks after the muscle injury performed poorly on the treadmill and in muscle strength studies, compared to placebo-treated mice.

Scientists also tested the drug in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy, since prednisone is normally given for this disease. Mice with muscular dystrophy that received weekly prednisone were stronger and performed better on the treadmill than those getting a placebo. When prednisone was given every day, the muscles atrophied and wasted.

McNally initiated the research because she wanted to understand how prednisone — which is given to treat individuals with a form of muscular dystrophy called Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy — prolongs patients’ ability to walk independently and stay out of a wheelchair.

“It’s been known that long-term daily treatment with prednisone also has the side effect of causing muscle wasting in many people,” McNally said. “So it has always been something of a medical curiosity that it is also used chronically to treat conditions like myositis (muscle inflammation) and Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy."

While years of being on the steroids cause growth suppression, osteoporosis and other bad side effects, boys with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy walk two to three years longer if they take steroids. Boys get the disease because it is on the X chromosome, and males have only one X chromosome.

“A typical boy with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy goes into a wheelchair at age 10; if he takes steroids, it’s age 13,” McNally said. “So in muscular dystrophy, there is definitely a benefit, but it’s a double-edged sword with all the side effects.”

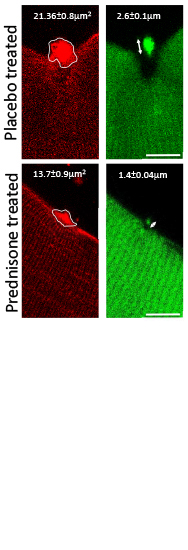

For the study, McNally and colleagues used high-resolution imaging to view the muscle’s ability to repair itself. This technique uses a laser to poke a hole in muscle cells. Then the muscle cell is observed in real time as it reseals the hole, a natural repair process.

Next, the scientists tested to see if steroids could boost the repair process.

“The steroids made muscle heal faster,” McNally said. “We were like, ‘Wow!’ It accelerated the repair in the muscle cells.”

For the second part of the study, scientists tested steroids in mice. They damaged the leg muscles in mice and noticed the mice receiving the steroids recovered more rapidly from injury.

“We showed steroid treatment, when given weekly, improves muscle performance,” McNally said.

Her work also implies normal muscle injury would improve more quickly by taking a weekly dose of steroids such as prednisone.

In the future, McNally would like to test steroids in humans and is considering studying it in forms of muscular dystrophy in which steroids would not normally be given, like Becker Muscular Dystrophy or Limb Girdle Muscular Dystrophy. Steroid treatment is not usually offered for these diseases since the side effects are thought to outweigh any potential benefit.

The study was funded in part by National Institutes of Health grants NIH U54 AR052646 and NIH RO1 NS047726, the Muscular Dystrophy Association, Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy and the American Heart Association.

- This article was originally published May 16, 2017.