A new form of electron microscopy allows researchers to examine nanoscale tubular materials while they are “alive” and forming liquids — a first in the field.

Developed by a multidisciplinary team at Northwestern University and the University of Tennessee, the new technique, called variable temperature liquid-phase transmission electron microscopy (VT-LPTEM), allows researchers to investigate these dynamic, sensitive materials with high resolution. With this information, researchers can better understand how nanomaterials grow, form and evolve.

“Until now, we could only look at ‘dead,’ static materials,” said Northwestern’s Nathan Gianneschi, who co-led the study. “This new technique allows us to examine dynamics directly — something that could not be done before.”

The paper was published online this week in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Gianneschi is the Jacob and Rosaline Cohn Professor of Chemistry in Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, professor of materials science and engineering and biomedical engineering in the McCormick School of Engineering, and associate director of the International Institute for Nanotechnology. He co-led the study with David Jenkins, associate professor of chemistry at University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

After live-cell imaging became possible in the early 20th century, it revolutionized the field of biology. For the first time, scientists could watch living cells as they actively developed, migrated and performed vital functions. Before, researchers could only study dead, fixed cells. The technological leap provided critical insight into the nature and behavior of cells and tissues.

“We think LPTEM could do for nanoscience what live-cell light microscopy has done for biology,” Gianneschi said.

LPTEM allows researchers to mix components and perform chemical reactions while watching them unfold beneath a transmission electron microscope.

We think LPTEM could do for nanoscience what live-cell imaging has done for biology.”

chemist

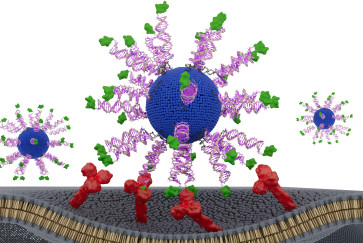

In this work, Gianneschi, Jenkins and their teams studied metal-organic nanotubes (MONTs). A subclass of metal-organic frameworks, MONTs have high potential for use as nanowires in miniature electronic devices, nanoscale lasers, semiconductors and sensors for detecting cancer biomarkers and virus particles. MONTs, however, are little explored because the key to unlocking their potential lies in understanding how they are formed.

For the first time, the Northwestern and University of Tennessee team watched MONTs form with LPTEM and made the first measurements of finite bundles of MONTs on the nanometer scale.

The research, “Elucidating the growth of metal-organic nanotubes combining isorecticular synthesis with liquid-cell transmission electron microscopy,” was supported by the National Science Foundation (award numbers ECCS-1542205 and DMR-1720139) and the Army Research Office (W911NF-18-1-0359).

The research was a collaboration between Gianneschi’s laboratory, which has expertise in transmission electron microscopy, and Jenkins’s laboratory, which has expertise in metal-organic nanotubes. Northwestern postdoctoral fellow Karthikeyan Gnanasekaran and University of Tennessee graduate student Kristina Vailonis served as the paper’s co-first authors. Gianneschi is also a member of the Simpson Querrey Institute, Chemistry of Life Processes Institute and the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center at Northwestern University.