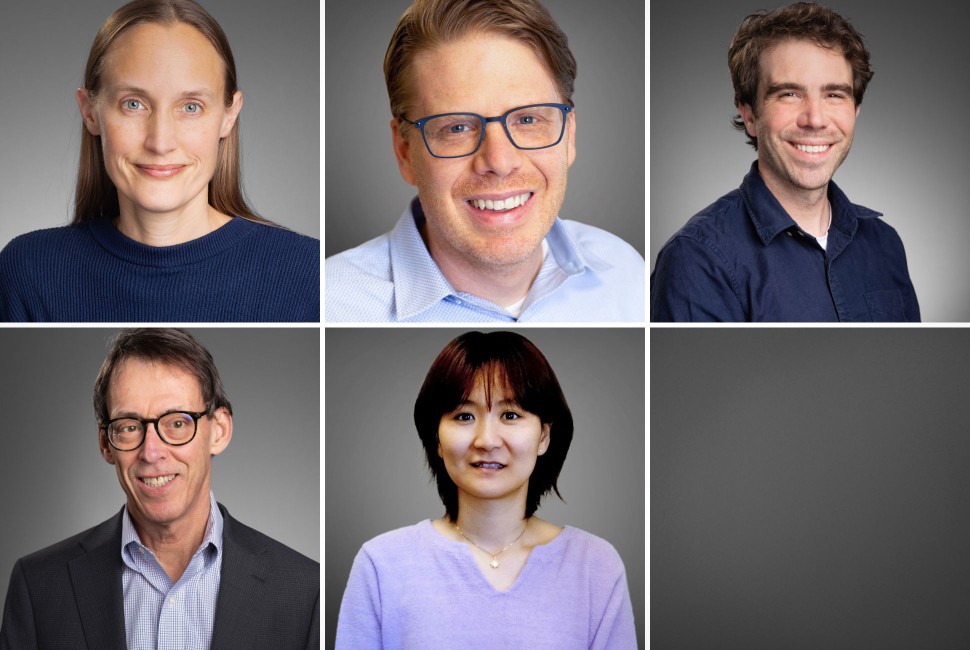

Five Northwestern faculty members — Caitlin Fitz, Michael Horn, Jonathan Emery, Peter Slevin and Yumi Shiojima — will be honored with 2025 University Teaching Awards. The annual recognition is given to professors who demonstrate excellence and innovation in undergraduate teaching.

“Every day, these faculty members imbue their work with intellect, creativity and heart, and the results are life-changing for our students,” Provost Kathleen Hagerty said. “I am so grateful for their talent and dedication. They keep the bar high at Northwestern, and they are why, year after year, we attract the best and brightest students.”

The recipients were nominated by the deans of the schools or colleges in which they have principal appointments. Honorees were selected by a committee chaired by the provost and made up of senior faculty members, University administrators and a student representative.

“Our students are positioned for success in an increasingly complex world thanks to the extraordinary level of commitment shown by our honorees — and our students are the first to say it,” Associate Provost for Undergraduate Education Miriam Sherin said. “The learning experiences these faculty create are both caring and effective. They make an extra effort to connect with their students. And that makes them stand out.”

The award includes a salary stipend for the next three years as well as funds for professional development. The term begins at the start of the 2025-2026 academic year.

The awards ceremony is Wednesday, May 21, in Guild Lounge on the Evanston campus. The event will be livestreamed.

Here are the 2025 honorees:

Caitlin Annette Fitz

Charles Deering McCormick Professor of Teaching Excellence

Caitlin Fitz believes that “the study of history has the potential to make us better people: more thoughtful, more humble, more humane.” She says that this conviction underlies her two primary goals every time she steps into a classroom: First, she wants students to “consider all sides of a story before forming an opinion on it; to remain intellectually flexible, broad-minded and even-handed.” Second, she wants students to become “more serious ethical thinkers, adept at reconstructing how generations of Americans have fought to define — and redefine — what was good and right and just.”

A historian of early America, Fitz explores early U.S. engagement with foreign communities and cultures, as well as the relationship between ordinary people and formal politics. “I want my students to appreciate the full range of things that past people cared about. Students often assume that history is mostly about presidents, elections and wars. But that’s not the half of it,” she says. “My early American survey class also encompasses topics like family planning, art and architecture, and the economics of whiskey and cider production.”

In her research seminars, Fitz places particular weight on writing, including sharing the process of getting published in a journal, from the critical evaluations of blind reviewers to the many queries, edits and proofs on the path to publication. “Students gasp at the level of rigor, detail and, yes, criticism,” she says. “My aim is to model mistake-making; to show that good writing requires great effort; and to pull back the curtain on how scholarship gets created.”

All of this and more is how, according to her department chair, Kevin Boyle, Fitz “in a quarter’s time, turns her students into practicing historians, trained in the highest standards of our discipline.” And why one student said, “Her lectures weren’t just well-organized, they were gifts to her students.”

Michael S. Horn

Charles Deering McCormick Professor of Teaching Excellence

Whether teaching classes like Introduction to Computer Programming, which attracts more than 200 students from across the University, or engaging undergraduate students to teach fifth-graders in Evanston public schools how to code through music (a partnership he forged to enable his students to put their skillset to use in the real world), Michael Horn emphasizes creativity and accessibility.

“I am inspired to build more inclusive and humanizing learning spaces that break out of the prerequisite mindset that often feels pervasive in higher education,” he says. He adds that, “among the many hopes that I have for my students is for them to see their time here as a starting point for lifelong learning.”

According to School of Education and Social Policy Dean Bryan Brayboy, Horn is “perhaps best known for teaching coding as a form of literacy” and “this pioneering idea not only makes coding accessible and fun but also influences students' understanding of complex topics and shapes how they view themselves.”

In Introduction to Computer Programming, Brayboy added, “Horn intentionally blends the artistic and technical by applying the Python programming language to fields such as art, music and data science. This approach helps students — who may later become journalists, doctors, performing artists or entrepreneurs — practice using one skill set to learn something new.”

Horn’s students appreciate this holistic view of learning. A senior who participated in Horn’s practicum in Evanston public schools said, “As I watched the children interact with my design and with each other, I was inspired by how combining technical and creative skills encouraged others to engage in active, collaborative learning, giving me hope for future generations.”

Another student, who took Tangible Interaction Design, in which students created an interactive museum exhibit that incorporated the technology they learned about in class, said, “Without a doubt, Professor Horn’s class fundamentally shifted the way that I think about technology, creativity and learning as a whole.”

Jonathan Emery

Charles Deering McCormick Distinguished Professor of Instruction

Jonathan Emery has a multidimensional approach to teaching materials science and engineering (MSE). His emphasis is on using “active and multimodal learning, intuition-building computational learning tools, and formative assessments that scaffold learning.”

For many students, though, it is Emery’s insistence on incorporating real-world applications into his curriculum that makes his classes stand out.

As one student shared, Emery “began every lecture with a ‘Why?’ slide, demonstrating the real-world significance of the topic. This intentional framing captivated our large, diverse class of nearly 100 students, ranging from biology majors to applied mathematics and various engineering disciplines.”

Emery also strives to make learning “personal” by encouraging students to “explore their own interests within the course’s framework.” He has redesigned many course projects to be “student-directed while maintaining alignment with key concepts and learning outcomes.” One of his students, a collegiate fencer, explored how the microstructural features of maraging steel give fencing blades the flexibility and strength essential for her sport — and that’s just one example of many.

In recent years, recognizing that emerging computational models could enhance the teaching of MSE, Emery, together with learning science/computer science Ph.D. student Jacob Kelter, co-led the revision of the introductory MSE curriculum grounded in computational modeling. In 2019, he and Kelter co-authored a low-cost electronic textbook and built a web-based learning platform that integrates computational models, videos, text, interactive exercises and other tools.

But Emery’s influence extends far beyond the classroom, as another student pointed out: “Although I did not have Professor Emery as an instructor for later courses in my materials science major, I continued to talk with him throughout my undergraduate career. He maintained an open door, not just for me to discuss my place in the program, but for all the students currently in materials science and those prospective students who were interested in the major.”

Peter Slevin

Charles Deering McCormick Distinguished Clinical Professor

Peter Slevin is a veteran journalist who had worked in more than 50 countries before he first taught at Northwestern in 2007. What he describes as a magic carpet ride of a career took him to Europe during the collapse of the Soviet Union and to Iraq in the aftermath of the U.S. invasion. He has touched God’s hand on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and he stood amid the crowds in Grant Park when Barack Obama won the presidency. Following stints at The Miami Herald and The Washington Post, he wrote an admired biography of Michelle Obama. Since 2019, he has been a contributing writer at The New Yorker.

In the classroom, teaching courses as varied as politics, foreign policy and the racial history of Evanston, Slevin encourages his students to start with questions, not answers, and to look for answers beyond the obvious. He asks students to challenge conventional wisdom and their own assumptions. He emphasizes rigor and depth, collaboration and creativity.

At the Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications, Slevin urges his students to get out of the classroom and into the field. He has led more than a dozen reporting trips in the U.S., where students interview voters, politicians and grassroots organizers, as well as trips to Cuba, Jordan and France. Without fail, he reports, students return with “tales to tell and stories to write.”

“Under Peter’s direction,” Charles Whitaker, Medill’s dean, writes, “a new generation of thoughtful and highly empathetic reporters — people who may restore trust in media — is being developed.”

For Slevin, the work starts in the classroom, where he draws praise for paying attention. A “baseline level of respect is what makes Professor Slevin’s teaching and reporting so unique,” a student wrote. “He respects every person as they are and considers what they have to say. To put it simply, he is extraordinarily present and empathetic.”

One recent graduate put it this way: “He’s responsible for the best things in my adult life.”

Yumi Shiojima

Charles Deering McCormick Distinguished Professor of Instruction

Yumi Shiojima teaches all four levels of Japanese with the goal of “connecting students to the world and developing their understanding and appreciation of the Japanese language, society and culture.” She emphasizes her commitment to helping students “build Japanese language proficiency: to observe and reflect, to communicate, to express themselves, and most importantly, to develop their own voice in Japanese.”

To help her students learn Japanese, one of the most difficult languages for English speakers, Shiojima uses both rigorous and creative approaches, which have included small-group and flipped classroom approaches. She has invited students to create a digital cookbook in Japanese and connected them to college students in Japan to promote language immersion. In Japanese Essay Writing, Shiojima seeks not only to improve students’ language proficiency, but also to serve “as a bridge to the students’ academic disciplines, allowing them to choose paper topics from their fields of study.”

Students appreciate Shiojima’s intense teaching style, describing her as “a demanding and kind professor.” One recent graduate said, “Even at the 100-level, Prof. Shiojima’s classes were rigorous, ensuring that we built a strong foundation in Japanese by paying meticulous attention to grammar and calligraphy. Having lived in Japan after graduation, I can confidently say that my Japanese handwriting is better than that of many native speakers, something I credit to her dedication to precision.”

Shiojima’s department chair, Melissa Macauley, points out that students often push through even the most difficult courses with the professor because they “love the warmth of her personality, her humor, her deep commitment to their improvement and the extraordinary amount of time she invests in them as students and human beings.”

As one student wrote, “She shows passion not just for the academic, but also the personal and emotional lives of her students. Her generosity is what keeps me in this class.”