On March 23, direct-to-consumer genetic testing company 23andMe announced it had filed for bankruptcy. The move came after the company, which generated genetic profiles based on saliva samples from customers, faced financial woes and a data breach in recent years.

California Attorney General Rob Bonta and others have urged users to delete their data in the wake of the bankruptcy filing over concerns about what may happen to consumers’ data. However, Northwestern genetic justice expert Sara Huston said she doesn’t share the same data-security concerns.

“I don’t think the highest bidder is going to be a foreign government or law enforcement, I think it’s going to be big pharma, so I say, so what if they get these data?” said Huston, a research assistant professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine whose research focuses on policy options for genetic testing applications in medicine and law enforcement and how genetic technologies affect individuals.

Huston also is the principal investigator of the Genetics and Justice Laboratory at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago where she explores the policy, science and ethics of genomic information for identification purposes. She co-leads Northwestern’s Global Fam DNA Working Group, which aims to pilot the use of DNA for a database to support reunifications of rescued Ukrainian children with their families and aid ongoing connections into the future.

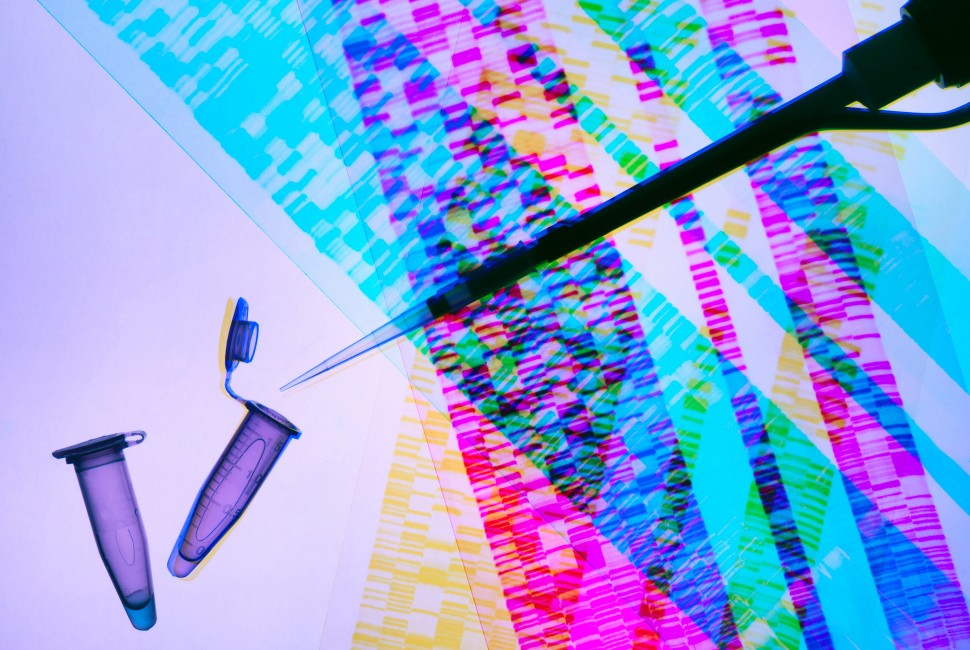

For more than 10 years, 23andMe has been collaborating with pharmaceutical companies, sharing de-deidentified aggregate data, which has led to significant discoveries, including hundreds of scientific papers, Huston said.

“The value in these data is not in the individual peoples’ results — the power is when you can look at genomic differences among people in aggregate,” Huston said. “There’s an enormous amount of human biology we can discover by connecting traits and genotypic data. 23andMe is a trove of such data.”

Even if the data goes somewhere else, Huston still sees the relative security risk as less pressing than for data held by others, such as social media companies.

“There’s a small risk that maybe a long-term care insurance company would want to profit off these data, but I don’t see them being the highest bidder,” Huston said. “If big pharma is not the highest bidder and it goes to a communications industry or social media industry, then maybe individualized data can be farmed. But I still don’t see it as a huge risk. Social media has far more intrusive information than genomic data. If you want to delete your data, this is your right and choice. But if you read this message on social media, then the data in your social media account is far more intrusive than a small sampling of your genetic code. I could be completely wrong, but I don’t see the sky falling.”