Using seawater, electricity and carbon dioxide (CO2), Northwestern University scientists have developed a new carbon-negative building material.

As Earth’s climate continues to warm, researchers around the globe are exploring ways to capture CO2 from the air and store it deep underground. While this approach has multiple climate benefits, it does not maximize the value of the enormous amounts of atmospheric CO2.

Now, Northwestern’s new strategy addresses this challenge by locking away CO2 permanently and turning it into valuable materials, which can be used to manufacture concrete, cement, plaster and paint. The process to generate the carbon-negative materials also releases hydrogen gas — a clean fuel with various applications, including transportation.

“We have developed a new approach that allows us to use seawater to create carbon-negative construction materials,” said Northwestern’s Alessandro Rotta Loria, who led the study. “Cement, concrete, paint and plasters are customarily composed of or derived from calcium- and magnesium-based minerals, which are often sourced from aggregates — what we call sand. Currently, sand is sourced through mining from mountains, riverbeds, coasts and the ocean floor. In collaboration with Cemex, we have devised an alternative approach to source sand — not by digging into the Earth but by harnessing electricity and CO2 to grow sand-like materials in seawater.”

Rotta Loria is the Louis Berger Associate Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering. Jeffrey Lopez, an assistant professor of chemical and biological engineering at McCormick, served as a key coauthor on the study.

Co-advised by Rotta Loria and Lopez, other Northwestern contributors include Nishu Devi, a postdoctoral fellow and lead author; Xiaohui Gong and Daiki Shoji, Ph.D. students; and Amy Wagner, former graduate student. The study also benefited from the contributions of key representatives from the Global R&D department of Cemex, a global building materials company dedicated to sustainable construction. This work is part of a broader collaboration between Northwestern and Cemex.

Tapping seawater, a naturally abundant resource

The new study builds on previous work from Rotta Loria’s lab to store CO2 long term in concrete and to electrify seawater to cement marine soils. Now, he leverages insights from those two projects by injecting CO2 while applying electricity to seawater in the lab.

“Our research group tries to harness electricity to innovate construction and industrial processes,” Rotta Loria said. “We also like to use seawater because it’s a naturally abundant resource. It’s not scarce like fresh water.”

To generate the carbon-negative material, the researchers started by inserting electrodes into seawater and applying an electric current. The low electrical current split water molecules into hydrogen gas and hydroxide ions. While leaving the electric current on, the researchers bubbled CO2 gas through seawater. This process changed the chemical composition of the water, increasing the concentration of bicarbonate ions.

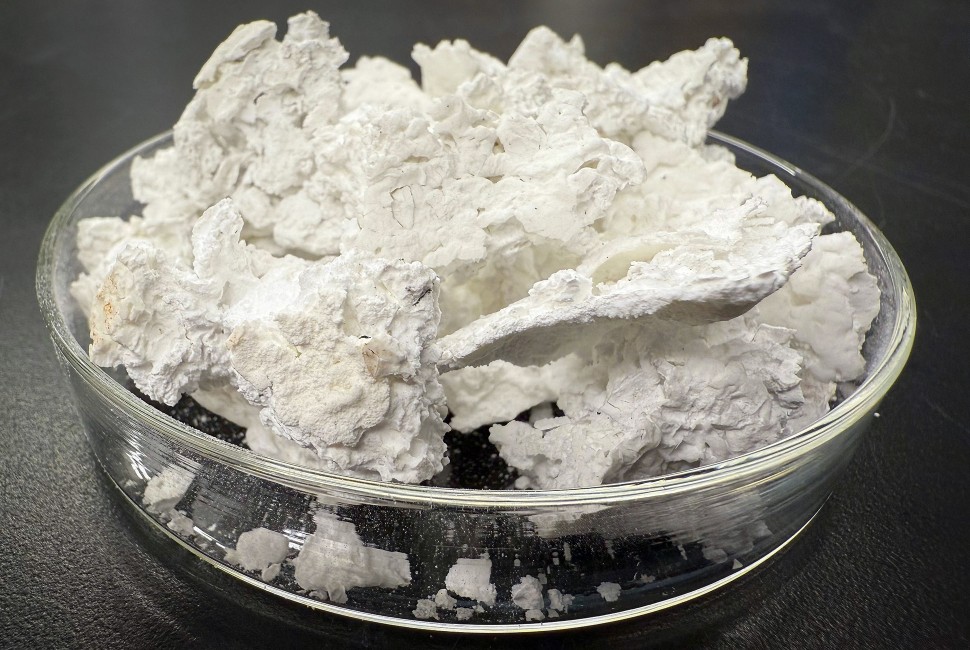

Finally, the hydroxide ions and bicarbonate ions reacted with other dissolved ions, such as calcium and magnesium, that occur naturally in seawater. The reaction produced solid minerals, including calcium carbonate and magnesium hydroxide. Calcium carbonate directly acts as a carbon sink, while magnesium hydroxide sequesters carbon through further interactions with CO2.

Rotta Loria likens the process to the technique coral and mollusks use to form their shells, which harnesses metabolic energy to convert dissolved ions into calcium carbonate. But, instead of metabolic energy, the researchers applied electrical energy to initiate the process and boosted mineralization with the injection of CO2.

“The appeal of such an approach is the attention that is being given to the ecosystem and using science to harness the elements in the contemporary environment to develop valuable products for several industries and preserve resources,” said Davide Zampini, vice president of global R&D at Cemex.