Hundreds of thousands of Americans with glaucoma are not receiving the care they need — and a new Northwestern University study suggests that race, income and where patients live play a major role in that gap.

Researchers found that Black, Hispanic and Asian American patients, as well as those from rural and economically distressed communities, are significantly less likely to receive optic nerve evaluations — a critical part of monitoring glaucoma progression — compared to white and urban patients.

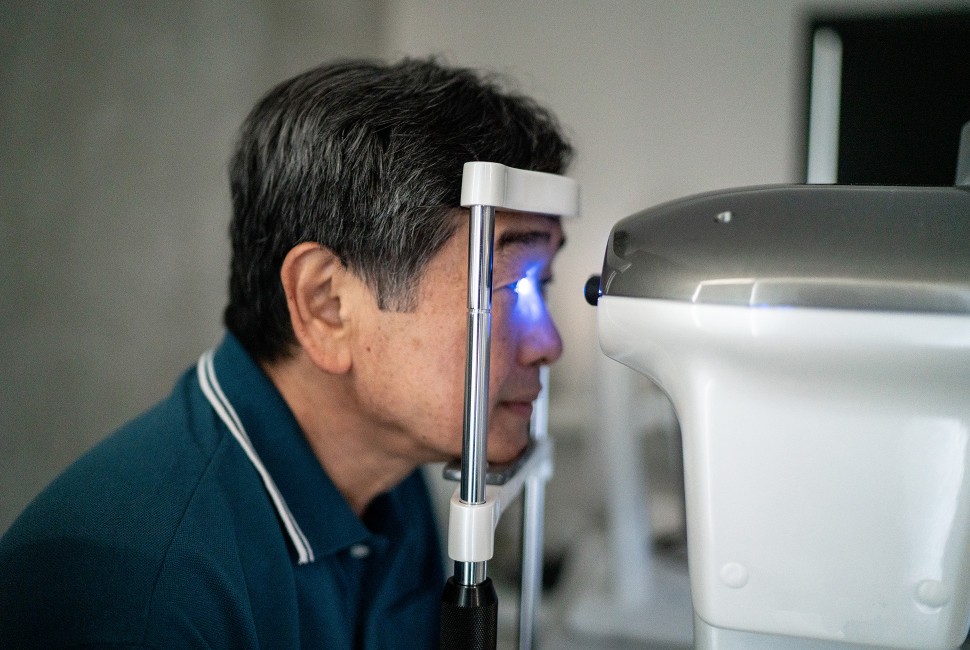

Glaucoma is a leading cause of irreversible blindness, affecting more than 3 million people in the U.S. and 76 million worldwide. Because the disease progresses gradually and often without symptoms, regular evaluations are essential for detecting damage before significant vision loss occurs.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends most patients with glaucoma undergo at least two follow-up visits per year, including an annual evaluation of the optic nerve. Yet, the study found that only 57% of glaucoma patients across all demographics received an optic nerve exam within three years following a glaucoma diagnosis.

Glaucoma is a leading cause of irreversible blindness and affects 76 million people worldwide.

“This is strikingly low,” said senior author Dustin French, a professor of ophthalmology and medical social sciences (determinants of health) at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “If nearly half of glaucoma patients aren’t getting the recommended follow-ups, that’s a serious failure in care. We need targeted solutions to ensure patients don’t slip through the cracks.”

The scientists found that the odds of receiving the recommended optic nerve follow-up exam were 56% lower for patients living in isolated rural communities compared to urban areas, 17% lower for Black patients compared with White patients, and 9% lower for patients residing in more impoverished communities.

“These disparities highlight an urgent need to address the social determinants of health that influence patient care,” said first author Kunal Kanwar, a third-year medical student at Feinberg. “Patients in rural and poor communities face significant barriers to care, which may lead to higher rates of irreversible vision loss.”

The study analyzed data from 13,582 adults with glaucoma treated at 12 major U.S. health systems over a nearly four year period using the SOURCE Ophthalmology Big Data Consortium. While previous research focused mainly on racial and ethnic disparities, this study used a novel approach to also calculate how geographic and economic factors influenced patient care.

The scientists incorporated the Distressed Community Index Score, which measures a community’s socioeconomic distress by zip code, to assess how neighborhood affluence impacted glaucoma monitoring. They also used RUCA codes, which classify U.S. census tracts by population density and other factors, to measure the effect of urban versus rural living on access to care.

The study identified several strategies to improve glaucoma care for vulnerable populations. Expanding tele-ophthalmology services, including programs like the Veterans Affairs’ TeleEye Care, could help patients in rural areas access care more easily.

Advancing technology for home monitoring could help patients track their condition without needing to visit a clinic. Improving transportation options and offering financial support for patients facing cost barriers could also increase access to care.

“Increasing access to remote monitoring and increasing provider incentives to serve rural and lower-income communities could make a real difference,” French said. “Future research will focus on testing these strategies to see which approaches work best.”

The study, published in the journal Translational Vision Science & Technology, was supported by the National Eye Institute and the nonprofit organization Research to Prevent Blindness.