We’ve all been there. Moments after leaving a party, your brain is suddenly filled with worries about what others were thinking. “Did they think I talked too much?” “Did my joke offend them?” “Were they having a good time?”

In a new Northwestern Medicine study published in Science Advances, scientists sought to better understand how humans became so skilled at thinking about what’s happening in other peoples’ minds. The findings could have implications for one day treating psychiatric conditions such as anxiety and depression.

The background: Evolutionary timelines

“We spend a lot of time wondering, ‘What is that person feeling, thinking? Did I say something to upset them?’” said senior author Rodrigo Braga. “The parts of the brain that allow us to do this are in regions of the human brain that have expanded recently in our evolution, and that implies that it’s a recently developed process. In essence, you’re putting yourself in someone else’s mind and making inferences about what that person is thinking when you cannot really know.”

The study found the more recently expanded parts of the human brain that support social interactions — called the social cognitive network — are connected to and in constant communication with a more ancient part of the brain called the amygdala.

The amygdala’s role

Humans’ common ancestor with lizards likely also had an amygdala, which is why it’s often referred to as our “lizard brain.” It’s typically associated with detecting threats and processing fear. A classic example of the amygdala in action is someone’s physiological and emotional response to seeing a snake: startled body, racing heart, sweaty palms. But the amygdala also does other things, Braga said.

“For instance, the amygdala is responsible for social behaviors like parenting, mating, aggression and the navigation of social-dominance hierarchies,” said Braga, an assistant professor of neurology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “Previous studies have found co-activation of the amygdala and social cognitive network, but our study is novel because it shows the communication is always happening.”

Within the amygdala, there’s a specific part called the medial nucleus that is very important for social behaviors. This study was the first to show the amygdala’s medial nucleus is connected to newly evolved social cognitive network regions, which are involved in thinking about other people. This link to the amygdala likely helps shape the function of the social cognitive network by giving it access to the amygdala’s role in processing emotionally important content.

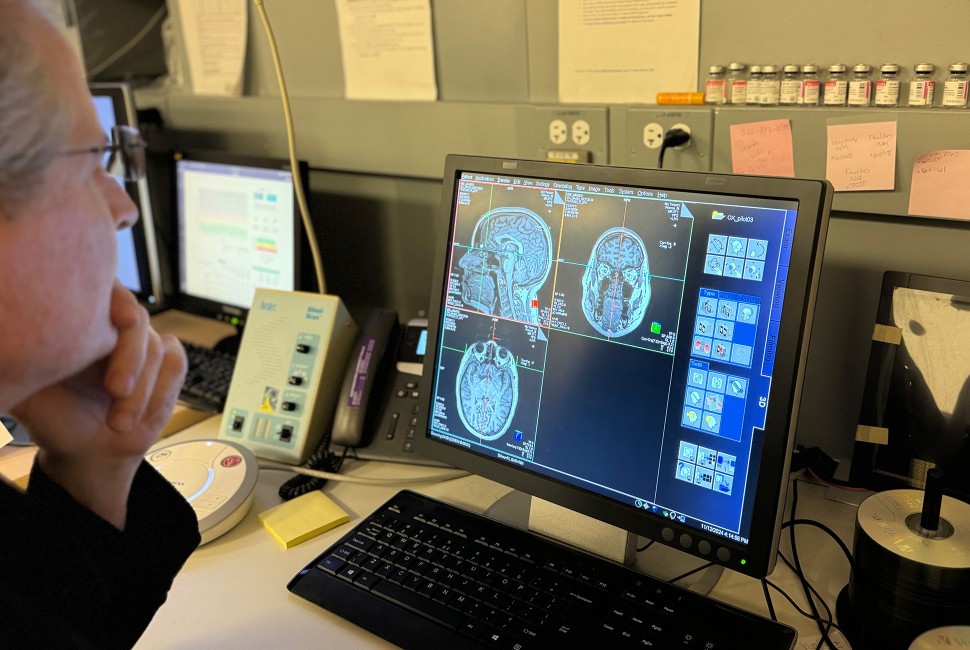

High-resolution brain scans were key

The researchers were able to make their discovery thanks to functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a noninvasive brain-imaging technique that measures activity by detecting changes in blood oxygen levels.

A collaborator at the University of Minnesota and co-author on the study, Kendrick Kay, provided the researchers with high-resolution fMRI data from six study participants as part of the Natural Scenes Dataset. These high-resolution scans enabled the scientists to see new details of the social cognitive network. The researchers then supplemented this with data collected at Northwestern’s Center for Translational Imaging, where participants performed tasks targeting social cognitive processes.

“We were able to identify network regions we weren’t able to see before,” said co-corresponding author Donnisa Edmonds, a neuroscience Ph.D. candidate in Braga’s lab at Northwestern. “That’s something that had been underappreciated before our study, and we were able to get at that because we had such high-resolution data.”

Potential treatment of anxiety, depression

Both anxiety and depression involve amygdala hyperactivity, which can contribute to excessive emotional responses and impaired emotional regulation, Edmonds said. Currently, someone with either condition could receive deep brain stimulation for treatment, but this means having an invasive, surgical procedure. Now, with this study’s findings, a much less-invasive procedure, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), might be able to use knowledge about this brain connection to target the amygdala by stimulating regions of the social cognitive network which sit on the brain surface. While researchers don’t yet know if this would have a beneficial effect, it presents an exciting future avenue of investigation, Braga said.

“Through this knowledge that the amygdala is connected to other brain regions — potentially some that are closer to the skull, which is an easier region to target — that means people who do TMS could target the amygdala instead by targeting these other regions,” Edmonds said.