With help from an experienced underwater cave-diving team, Northwestern University researchers have constructed the most complete map to date of the microbial communities living in the submerged labyrinths beneath Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula.

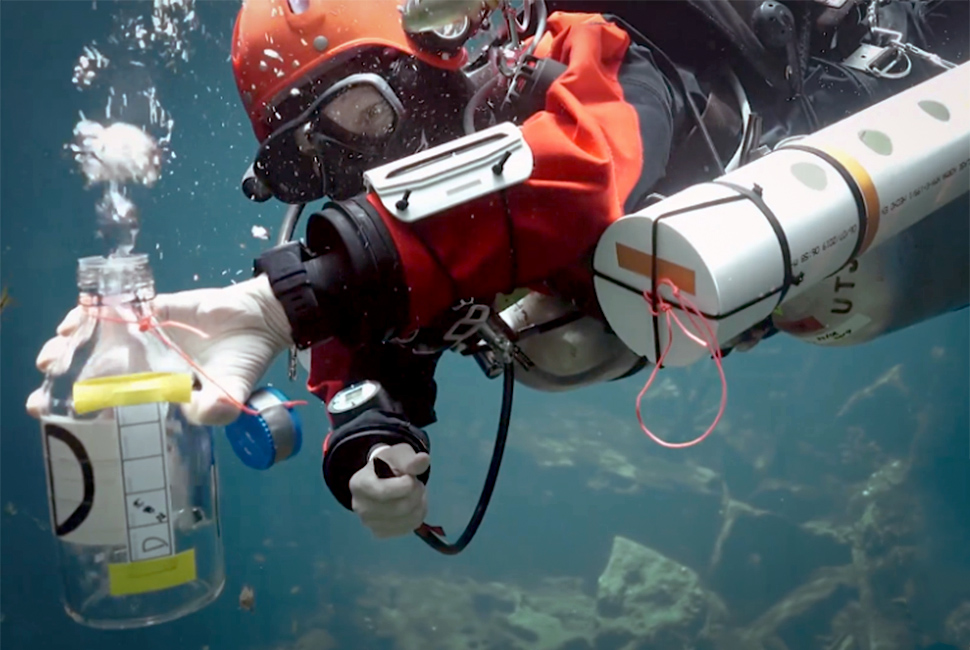

Although previous researchers have collected water and microbial samples from the cave entrances and easily accessible sinkholes, the Northwestern-led team reached the deep, dark passageways of unlit waters to better understand what can survive inside this unique underground realm.

After analyzing the samples, the researchers noted a system rich with diversity, organized into distinct patterns. Similar to a stereotypical high school lunchroom, microbial communities within the cave system tend to cluster into well-defined cliques. But one family of bacteria (Comamonadaceae) acted as a popular social butterfly — appearing at nearly two-thirds of the “cafeteria tables.” The findings hint that Comamonadaceae is the ecological linchpin of the broader community.

“This is certainly the most expansive microbial survey across this part of the world,” said Northwestern’s Magdalena R. Osburn, who led the study. “These are incredibly special samples of underground rivers that are particularly difficult to obtain. From those samples, we were able to sequence the genes from microbial populations that live in these sites. This underground river system provides drinking water for millions of people. So, whatever happens with the microbial communities there has the potential to be felt by humans.”

A geobiology expert, Osburn is an associate professor of Earth and planetary sciences at Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. Northwestern alumnus Matthew Selensky led this project as a part of his dissertation when he was a graduate student in Osburn’s laboratory. Study co-author Patricia Beddows,professor of Earth and planetary sciences at Weinberg, led the cave-diving expedition and leveraged her decades of experience working on these caves. Other Northwestern co-authors include Andrew Jacobson, professor of Earth and planetary sciences, and former graduate student Karyn DeFranco, who focused on the geochemistry.

Located primarily in southeastern Mexico, the extensive Yucatán carbonate aquifer is pockmarked by numerous sinkholes leading to a complex web of underwater caves. Hosting a diverse, yet understudied microbiome, the underwater network contains areas of freshwater, seawater and mixtures of both. The system also includes a variety of zones — from pitch-black, deep pits with no direct openings to the surface to shallower sinkholes sparkling with sunlight.

“The Yucatan platform is essentially a Swiss cheese of cave conduits,” Osburn said. “We were curious which microbes are found together when we look across the whole system versus which microbes are found within one ‘neighborhood.’”