If you added up all the microbes living deep below Earth’s surface, the amount of biomass would outweigh all life within our oceans.

But because this abundant life is so difficult to reach, it is widely understudied and incompletely understood. By accessing the deep underground through a former goldmine-turned-lab in South Dakota’s Black Hills, Northwestern University researchers have pieced together the most complete map to date of the elusive and unusual microbes beneath our feet.

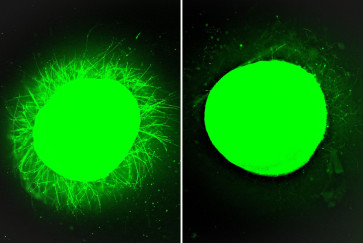

In total, the researchers characterized nearly 600 microbial genomes — some of which are new to science. Out of this batch, Northwestern geoscientist Magdalena Osburn, who led the study, says most microbes fit into one of two categories: “minimalists,” which have streamlined their lives by eating the same thing all day, every day; and “maximalists,” which are ready and prepared to greedily grab any resource that might come their way.

The study has been accepted by the journal Environmental Microbiology. An early version of the manuscript is now available online.

Not only does the new study expand our knowledge of the microbes living deep within the subsurface, it also hints at potential life we someday might find on Mars. Because the microbes live on resources found within rocks and water that are physically separate from the surface, these organisms also potentially could survive buried within Mars’ dusty red depths.

“The deep subsurface biosphere is enormous; it’s just a vast amount of space,” said Osburn, an associate professor of Earth and planetary science at Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. “We used the mine as a conduit to access that biosphere, which is difficult to reach no matter how you approach it. The power of our study is that we ended up with a lot of genomes, and many from understudied groups. From that DNA, we can understand which organisms live underground and learn what they could be doing. These are organisms that we often can’t grow in the lab or study in more traditional contexts. They are often called ‘microbial dark matter’ because we know so little about them.”

A portal into the Earth’s crust

For the past 10 years, Osburn and her students have regularly visited the former Homestake Mine in Lead, South Dakota, to collect geochemical and microbial samples. Now called the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF), the deep underground laboratory hosts a number of research experiments across a range of disciplines. In 2015, Osburn established six experimental sites, collectively called the Deep Mine Microbial Observatory, throughout SURF.

“The mine is now a facility dedicated to underground science,” Osburn said. “Researchers mostly perform high-energy particle physics experiments. But they also let us study the deep biospheres that live within the rocks. We can set up experiments in a controlled, dedicated site and check on them months later, which we would not be able to do in an active mine.”