Have you ever wished that you could reach into a museum cabinet halfway around the world to pick up a sculpture, or listen to an expert tell the story behind it?

An innovative new exhibit at Northwestern’s Herskovits Library of African Studies (on the fifth floor of University Library) enables visitors to do just that, with the help of both augmented and virtual reality.

“Augmented Curiosities: Virtual Play in African Pasts and Futures” is open through Fall Quarter. For those who can’t visit in person, a digital version of the exhibit is also available online.

The exhibition was designed to be incredibly interactive — and to imbue objects with more personal stories — than had been possible in the past, according to Craig Stevens, a Ph.D. student in anthropology, who curated the exhibit.

“My practice is about animating objects and telling stories through objects,” he said. “When it comes to curation, that impulse makes me search for ways to make stories dynamic outside of texts and articles.”

The exhibit’s title is meant to start conversations. Historically, “cabinets of curiosity” were private exhibits that European aristocrats assembled and displayed to demonstrate their global mobility and taste, Stevens said.

Though this practice laid the foundation for modern museum collecting, it also problematically labelled African and other objects as “curiosities” and made access to them exclusive. By contrast, this exhibit makes objects more accessible, and exhibits them with awareness of their cultural context.

From hundreds of images, a digital version for visitors around the world

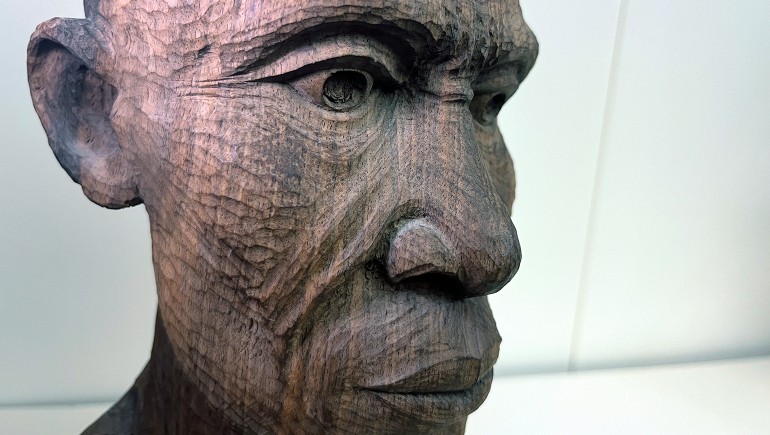

Six objects from the library’s vast collection of material culture — which is the largest separate Africana collection in existence at any university, according to its website — are featured in the exhibit. They include a Yoruba statuette, a Nuna smoking pipe, and a beaded Zulu fertility doll designed in part to raise awareness about HIV/AIDS, along with memorabilia from the World Cup in South Africa in 2010 and other objects.

Each object is physically present and described with a traditional label in a display case, but then also digitally reconstructed through photogrammetry — the process of using hundreds of images stitched together by software — so that a piece can also be manipulated by visitors around the world in the virtual space.

The digital renderings, along with 3D-printed models of the objects that replace them for security at night and on weekends, were created through a collaboration between the Herskovits Library and Northwestern IT’s Media & Technology Innovation unit.

“There is no limit to the ways technology can support innovative scholarship, enabling scholars to explore new dimensions in their work,” said Rodolfo Vieira of Media & Technology Innovation. “We’re thrilled to be able to collaborate with students like Craig, who exemplifies this by leveraging augmented and virtual reality to bring this exhibit to new and different audiences.”

The partnership has spurred new interest in the Herskovits collection from people across campus, according to Esmeralda Kale, the library’s George and Mary LeCron Foster Curator, who is a proponent of student-curated exhibits and helped facilitate the project.

“We have seen people in this library from Northwestern we’ve never seen before, who want to talk about virtual reality, augmented reality, and have those new conversations in this space,” she said.

So, what, exactly, do users see in the exhibit?

To the left and right of the display case are pedestals where visitors can use an iPad or personal device to scan QR codes and choose an object to virtually place on the pedestal, allowing them to walk around the 3D rendering while learning more and examining it from different angles. This is the augmented reality portion of the exhibit.

Stevens says it's “like Pokémon Go” in that you see the object superimposed on your reality and can interact with it via a screen.

Behind the case is a separate viewing area, where visitors can don a headset that allows them to “reach” into a digital facsimile of the display case and pick up and interact with the objects virtually in an immersive environment.

In the background, videos play in which Northwestern community members who have scholarly expertise about the objects, a personal connection to the objects through culture or geography, or both discuss the objects’ stories. This is the virtual reality portion of the exhibit.