Although astrophysicists have never sensed supermassive black hole binary systems, a galaxy-sized detector composed of dead stars is hot on their trail.

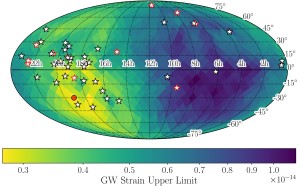

In a new Northwestern University-led study, astrophysicists crunched 12.5 years of data from 45 dead stars (called pulsars) to set the best limits yet on the gravitational wave signatures emitted from pairs of monster black holes. Knowing these limits will help astrophysicists constrain the number of binaries existing in the nearby universe, confirm or deny existing binary candidates and, someday, detect gravitational waves from these complex pairs.

In another breakthrough, the study also found that when searching for pairs of supermassive black holes, researchers need to account for the steady hum of background noise made by the symphony of gravitational waves from all the supermassive black hole binaries in the universe.

The study was accepted by The Astrophysical Journal Letters and will be published this summer. A preprint of the manuscript is available here.

“We genuinely think that detection of a supermassive black hole binary through gravitational waves is right around the corner,” said Northwestern’s Caitlin Witt, who led the study. “That would be an important discovery for many scientific fields. It would enable us to perform further experiments like testing gravity to explore whether supermassive black hole binaries evolve the way we think they do, and it will teach us how to look for them in future surveys. We also will be able to look back through cosmic time and trace the history of the universe in which we live.”

Witt is the inaugural CIERA-Adler Postdoctoral Fellow at Northwestern’s Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA) and the Adler Planetarium.

Too big to detect

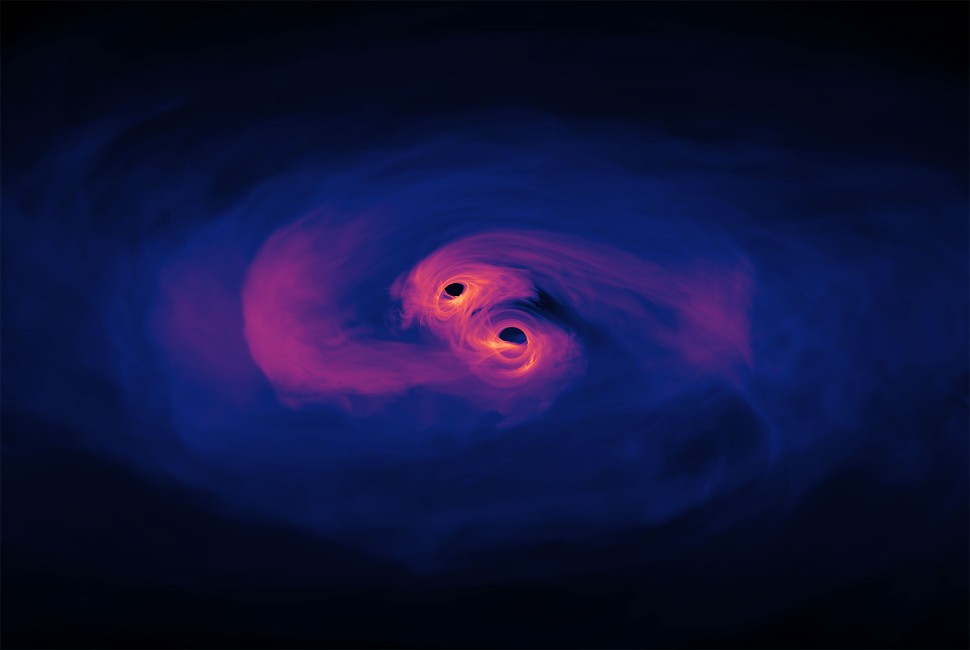

Located in the center of most galaxies, supermassive black holes can be several billion times the mass of our sun. Compared to typical stellar-mass black holes, which are 10 to 100 times more massive than our sun, supermassive black holes are unfathomably gigantic.

When two galaxies — each with a central supermassive black hole — merge together, it can create a binary system of these monstrous black holes.

“Someday, our galaxy will collide with the Andromeda galaxy,” Witt said. “Millions of years after that, the black holes eventually find each other to form a little buddy system. Detecting gravitational waves from systems like these will help us understand how galaxies interact and how the universe evolves.”