Understanding the relationship between the individual and the wider world in which that person exists is a question that has propelled most of Deborah Cohen’s research.

And what better subjects upon which to examine the wider world’s impact than the gutsy group of American reporters she chronicles in her latest book “Last Call at the Hotel Imperial: The Reporters Who Took on a World at War” (Random House).

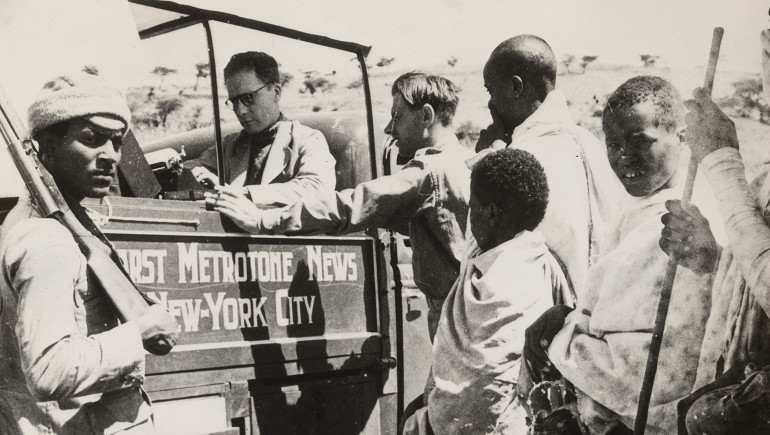

John Gunther, H.R. Knickerbocker, Vincent “Jimmy” Sheean and Dorothy Thompson chased down interviews with the most imposing political figures of their day — including Mussolini, Hitler, Gandhi and Nehru — to inform readers back home about the world-shaping events unspooling abroad. These prototypical foreign correspondents also experimented with Freudian psychoanalysis, had affairs and argued about everything from love and war to death and politics.

Cohen, chair of Northwestern’s history department and a comparative historian of Britain and Germany, had already published three books about European history. The experience of studying the correspondence from these reporters’ archives, however, enabled Cohen to see the 1920s and ’30s from a new perspective.

“We often tell our history from the point of explaining what already happened. I would have never given a lecture about the ’30s with 1934 Vienna at the center of it. But for these people, when the battle of social democracy and fascism is being joined, this is the place where the light bulb goes on and the shape of the future is becoming clear to them.”

Upon release in March 2022 “Last Call” quickly topped the “Best of” lists at The New York Times, the New Yorker, the Financial Times and Vanity Fair, and peer acclaim has followed. In 2023, Cohen was awarded the prestigious Lynton History Prize from the Columbia Journalism School and Nieman Foundation, as well as the Goldsmith Prize for a best book on democratic governance from Harvard University. In November of 2023, she will receive the Phi Beta Kappa Society's Ralph Waldo Emerson Award. The $10,000 prize honors a scholarly study that contributes significantly to interpretations of the intellectual and cultural condition of humanity.

Northwestern Now spoke with Cohen about how she learned to write like a crackerjack reporter from the ’30s, which character she most identifies with and why the book is resonating with contemporary readers.

Your writing style matches the characters so eloquently. How did you adapt it for the period?

It was an experiment. Usually when I’m in an archive I’m looking at correspondence between parties that might run over 20 years. But you don’t get the multi-vocality that comes from a group of friends. As I sat in these archives, it was like I had dropped into this set of people who were outrageous, and perspicacious, and daring and reckless, and in some ways ruinous to themselves and to others. I could hear them, and I wanted to try to create that for the reader.

Did you ever want to be a journalist?

Yes, desperately! I just didn’t have the guts or the bravery or all the things that you need to be a journalist and be willing to knock on strangers’ doors and ask them questions. I think that’s another reason why these archives are so fantastic. All the questions I felt I would want to ask them had they been here, I would take notes and say, I wonder where, or I wonder why, or I wonder how? And so many of those questions would be answered in the letters. It felt magical, that entire process of research.