Spending the first decade of your life in hiding with your family, using fake names and being on the run from the FBI is far from a typical childhood. But that was the reality for School of Communication professor Zayd Dohrn.

Dohrn — a playwright and director of the MFA in Writing for the Stage and Screen in the department of radio/television/film — is the son of Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers. In the late 1960s through the early 1970s, Dorhn and Ayers were a part of the radical left-wing organization called The Weather Underground, a counterculture group of young activists.

Now retired, Bernardine Dohrn was founding director of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law’s Children and Family Justice Center.

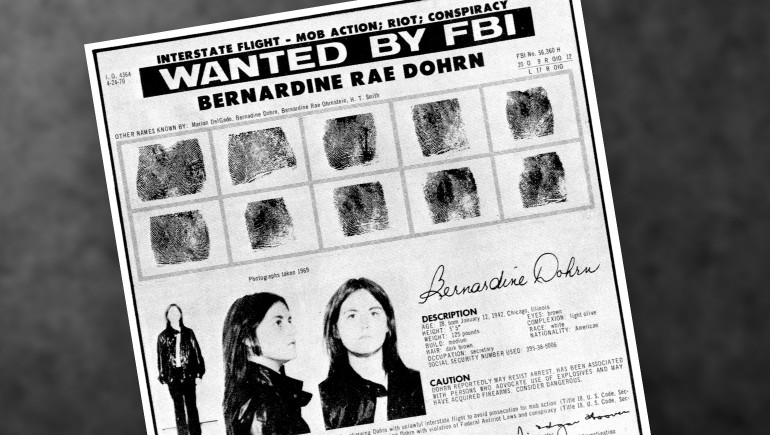

Fifty years ago this month, The Weather Underground bombed the Pentagon as part its pursuit of what it called “radical change through any means necessary.” The group often joined with Black militant groups in an attempt to build a revolution in America. As a leader of the group, Bernardine Dohrn was on the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted list for several years.

Zayd Dohrn recounts his family’s unique and intriguing story in a new 10-episode podcast called “Mother Country Radicals.” The series, created by Crooked Media and Audacy, features his parents in their own voices, interviews with other Weather Underground members such as Jeff Jones and Kathy Boudin, and activists including Angela Davis and Fred Hampton.

Dohrn wrote the docu-series and narrates this telling of his family’s history. The series made its world premiere at the 2022 Tribeca Film Festival as an Audio Storytelling Official Selection.

Related audio: Listen to the trailer for "Mother Country Radicals."

Dohrn spoke with Northwestern Now about the lessons his family learned during that time of social and political unrest and how, in many ways, the revolution his parents led mirrors the racial reckoning and protests of today.

How did the idea of a podcast come about?

I’ve written a lot of scripts and screenplays but never really delved into this story, partly because it just felt too obvious to me or too close to what I already knew. Then, a couple things happened — one personal and the other political. My parents are getting older, and I might not have that many more chances to ask them some of the questions that had been on my mind and preserve some of the stories. And then simultaneously, the political thing happened. We were in the middle of the pandemic, and George Floyd was murdered by police. I was thinking a lot about that kind of moment of racial reckoning and about police violence, and about how white people can be comrades to Black people dealing with the violence of the state.

I think most of the world who knows this story doesn’t realize how directly the work of The Weather Underground and other activists was about responding to police violence — the murder of Fred Hampton and the crackdown on the Black Panther Party. And from there I got interested in this idea of what does it mean for people who want to stand against white supremacy. What does it mean to really commit yourself to doing that? What are some of the mistakes they made and the lessons that we can take from some of those mistakes?

When did you realize who your mom and dad were beyond your parents?

When I was growing up, I knew the FBI was chasing us. I don’t think I knew what the FBI was exactly, but they described it to me in ways a kid could understand. They talked about Robin Hood. They talked about stealing from the rich and giving to the poor. They talked about Luke Skywalker like fighting an evil empire. I knew that we were hiding. I knew that we used fake names. As strange as that all sounds, it actually felt normal because it was the only thing I’d ever known.

When I was about five years old, we turned ourselves in, and my mom went to jail. I was certainly very aware when I was visiting her in jail that that was odd and that most of my friends were not in that situation. But it wasn’t until I was a teenager that I started to look back once we reintegrated into society. My mom was a lawyer, and my dad was a professor. People would start to say, ‘Oh, wait, that’s your mom’, or I would find her wanted poster, or something like that. And I think I started to put it together as a teenager how really abnormal our lives had been.