A Northwestern University-led team of astrophysicists has developed the first-ever full 3D simulation of an entire evolution of a jet formed by a collapsing star, or a “collapsar.”

Because these jets generate gamma ray bursts (GRBs) — the most energetic and luminous events in the universe since the Big Bang — the simulations have shed light on these peculiar, intense bursts of light. Their new findings include an explanation for the longstanding question of why GRBs are mysteriously punctuated by quiet moments — blinking between powerful emissions and an eerily quiet stillness. The new simulation also shows that GRBs are even rarer than previously thought.

The new study was published today (June 29) in Astrophysical Journal Letters. It marks the first full 3D simulation of the entire evolution of a jet — from its birth near the black hole to its emission after escaping from the collapsing star. The new model also is the highest-ever resolution simulation of a large-scale jet.

“These jets are the most powerful events in the universe,” said Northwestern’s Ore Gottlieb, who led the study. “Previous studies have tried to understand how they work, but those studies were limited by computational power and had to include many assumptions. We were able to model the entire evolution of the jet from the very beginning — from its birth by a black hole — without assuming anything about the jet’s structure. We followed the jet from the black hole all the way to the emission site and found processes that have been overlooked in previous studies.”

Gottlieb is a Rothschild Fellow in Northwestern’s Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA). He coauthored the paper with CIERA member Sasha Tchekhovskoy, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences.

Weird wobbling

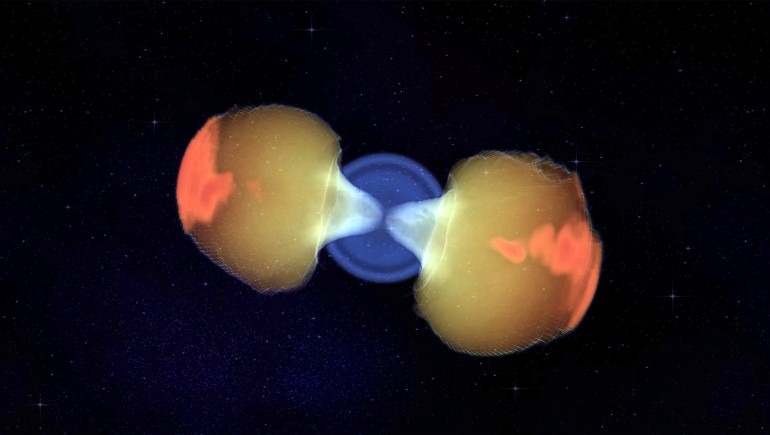

The most luminous phenomenon in the universe, GRBs emerge when the core of a massive star collapses under its own gravity to form a black hole. As gas falls into the rotating black hole, it energizes — launching a jet into the collapsing star. The jet punches the star until finally escaping from it, accelerating at speeds close to the speed of light. After breaking free from the star, the jet generates a bright GRB.

“The jet generates a GRB when it reaches about 30 times the size of the star — or a million times the size of the black hole,” Gottlieb said. “In other words, if the black hole is the size of a beach ball, the jet needs to expand over the entire size of France before it can produce a GRB.”

Due to the enormity of this scale, previous simulations have been unable to model the full evolution of the jet’s birth and subsequent journey. Using assumptions, all previous studies found that the jet propagates along one axis and never deviates from that axis.

“The jet generates a GRB when it reaches about 30 times the size of the star — or a million times the size of the black hole. In other words, if the black hole is the size of a beach ball, the jet needs to expand over the entire size of France before it can produce a GRB.” — Ore Gottlieb, astrophysicist

But Gottlieb’s simulation showed something very different. As the star collapses into a black hole, material from that star falls onto the disk of magnetized gas that swirls around the black hole. The falling material causes the disk to tilt, which, in turn, tilts the jet. As the jet struggles to realign with its original trajectory, it wobbles inside the collapsar.

This wobbling provides a new explanation for why GRBs blink. During the quiet moments, the jet doesn’t stop — its emission beams away from Earth, so telescopes simply cannot observe it.

“Emission from GRBs is always irregular,” Gottlieb said. “We see spikes in emission and then a quiescent time that lasts for a few seconds or more. The entire duration of a GRB is about one minute, so these quiescent times are a non-negligible fraction of the total duration. Previous models were not able to explain where these quiescent times were coming from. This wobbling naturally gives an explanation to that phenomenon. We observe the jet when its pointing at us. But when the jet wobbles to point away from us, we cannot see its emission. This is part of Einstein’s theory of relativity.”