In a new, rare study of direct brain recordings in children and adolescents, a Northwestern Medicine scientist and colleagues from Wayne State University have discovered as brains mature, the precise ways by which two key memory regions in the brain communicate make us better at forming lasting memories. The findings also suggest how brains learn to multitask with age.

The study was published Feb. 15 in Current Biology.

Historically, a lack of high-resolution data from children’s brains have led to gaps in our understanding of how the developing brain forms memories. The study innovated the use of intracranial electroencephalogram (iEEG) on pediatric patients to examine how brain development supports memory development.

The scientists found a link between how the brains of people aged 5 to 21 were developing and how well they were able to form memories throughout that 16-year period. For example, younger children, whose brains were not as developed as the adolescent participants, weren’t able to form as many memories as some adolescents.

By understanding how something comes to be — memory, in this instance — it gives us windows into why it eventually falls apart.”

Corresponding author

“Human memory develops throughout childhood, peaks in your 20s and, for most people, declines with age, even in those who don’t develop dementia."

To address this, her work focuses on the lifespan of memory to provide a holistic approach to understanding brain development and memory, which is why this study focused on pediatric patients.

Rhythms of key memory regions of the brain

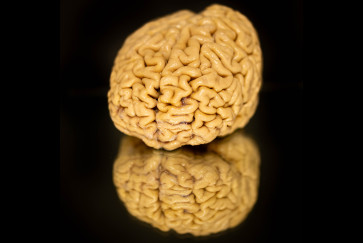

The study focused on communication between two regions of the brain that play a key role in supporting memory formation: the medial temporal lobe (MTL) and prefrontal cortex (PFC). To learn how these regions talk to one another, the scientists analyzed two brain signals — a slowly oscillating brain wave and a faster oscillating one — that enable communication between regions. The rhythms dictated whether a memory was successfully formed and differentiated top-performing adolescents from lower-performing adolescents and children.

Pioneering intracranial EEG in pediatric patients

The participants in the study were already undergoing brain surgery for another reason (usually to treat their epilepsy), and the scientists capitalized on this rare opportunity to examine data from electrodes placed directly on the exposed surface of the brain.

Following brain surgery, patients spent a week in the hospital for monitoring. This is when Johnson’s team conducted its studies, having the participants look at pictures of scenes to see how well they remembered them. The research team presented them with the same images again and new scenes they hadn’t yet seen (e.g., a different image of an outdoor area) to observe age-related differences in how well study participants remembered what they’d seen.

Our brains learn to multitask with age

Another novel finding in the study is that there appear to be age differences in fast and slow theta oscillations—rhythms in the brain that help with cognition, behavior, learning and memory. The slow theta frequency slows down with age, and the fast gets faster.

“These rhythms seemed to diverge with age so that they were similar in 5-year-olds and different in 20-year-olds,” Johnson said. “The fact that key memory regions are interacting at both frequencies suggests how your brain is learning to multitask as you get older.”

This research, which Johnson conducted while she was at her former collaborating institution, Wayne State University, provides the foundation of a research program Johnson is currently launching in collaboration with the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago.

Noa Ofen of Wayne State University is the study’s senior author.