Ahead of the first face-to-face meeting today between senior U.S. and Chinese officials since President Joe Biden took office, global affairs experts from Northwestern University break down the renewed policy posture toward China and the intricacies of pushing back on the Asian giant’s ambitions.

On March 12, President Biden convened virtually with the prime ministers of Japan, Australia and India, bringing together for the first time heads of state to reinvigorate the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue or the “Quad.”

In a joint statement, the group vowed to manufacture one billion COVID-19 vaccine doses by 2022. It also called for a free and open Indo-Pacific, a strategic concept linking both the Indian and Pacific oceans to guarantee freedom of navigation and deter threats to commerce passing through their waterways.

The Quad, however, is seen by some experts as a narrow effort to unify players in the region, especially when compared to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a more comprehensive and inclusive agreement.

“This is a much weaker attempt at trans-Pacific engagement to counter the rise of China than was the Trans-Pacific Partnership,” said Annelise Riles, executive director of the Buffett Institute for Global Affairs at Northwestern University.

“TPP included Asia-Pacific societies together from the bottom up. It was an ideal, like the European Union, of trying to bring nations together through trade. Here, there is no such grand ambition. The alliance is so far merely tactical, and very top down,” Riles said.

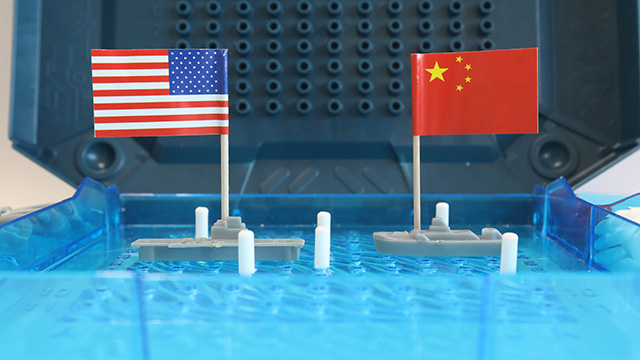

This is Biden’s first significant foreign policy push, and it’s aimed at curbing China’s growing influence in the South China Sea, a critical artery of international trade and a bastion of natural resources.

According to the Congressional Research Service, around $3.4 trillion in ship-borne commerce passes through the area each year, including 30% of global maritime crude oil.

It is home to an estimated 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Other countries in the region also vie for fisheries and other resources.

This week, both Secretary of State Anthony Blinken and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin embarked on a trip to Asia, shuttling between Japan, South Korea and India, further fortifying the U.S. commitment to allies in the region.

The TPP petered out, experts say, because it didn’t actively include ordinary people.

“Any Pacific alliances must engage civil society,” Riles said.

“TPP failed because ordinary people did not understand its purpose or trust the negotiators. The Quad could also fall prey to nationalism in any of the four countries if the public is not engaged.”

China’s increasingly critical role in the global economy has also created dependencies that are impervious to change.

“The group is severely limited by the reliance of its member countries on China as a customer, a source of goods, and a partner in many other endeavors,” said Ian Hurd, professor of political science and director of the Weinberg College Center for International and Area Studies at Northwestern.

“It’s impossible to imagine the Quad expanding to NATO-scale because of the fundamental co-dependence among China, the U.S., Japan, Australia and India in the world economy,” he said.

Hurd said these countries may not be willing to use actual tools of influence that they have. It’s hard to imagine, for example, Australia impeding sales of minerals to China or the U.S. denying access to its markets. And the U.S., Hurd added, is unlikely to persuade China to give up its effort to control maritime space.

India’s inclusion in the group could also be a signal that a new player is challenging China’s long-held position as the world’s factory.

“This alliance definitely counterbalances the reliance on China, but Indian manufacturing capability as stated does not seem new,” said Achal Bassamboo, a supply chain expert and professor of operations at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern.

“Before Covid, India was already producing 60% of the world's vaccines and has been a hub for biopharma manufacturing at low cost. Before the vaccine was discovered, it was projected that India would play a key role in vaccination due to the capacity it already has in this space. Perhaps the novelty of the talks is sharing of information which can allow these facilities to act as contract manufacturers for established drugs and speed up the availability of the vaccine,” Bassamboo said.

The Quad is also emphasizing its democratic nature — the four members all have freely elected governments. However, India, the world’s largest democracy, is not without blemishes.

“Narendra Modi’s government has built a climate of intolerance and trashed values of freedom, inclusion and democracy,” said Rajeev Kinra, associate professor of history at Northwestern.

“I think the Quad should be leveraged to pressure Modi to live up to the values expressed in the joint statement, let alone the Indo-Pacific,” Kinra said.

While none of the member states formally said that this is an anti-Chinese alliance, it remains defined by a shared interest in countering its rise in the region.

“It is challenging to build up an alliance solely on a common threat. Successful alliances almost always are built on a shared history or on shared cultural values,” said Riles.

Hurd agrees.

“It is a single-issue coalition dressed up in the costume of globalism, an opportunistic mini-multilateralism,” he said.