“We really have to think about translation as an act of interpretation.”

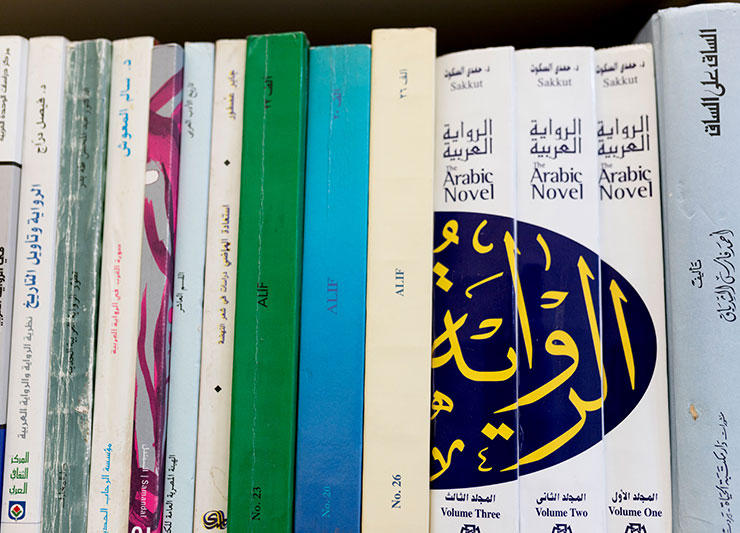

English professor Rebecca Johnson pulls the Arabic version of Victor Hugo’s “Les Misérables” from her bookshelf. It’s a tiny, pocket-sized book, 178 pages in total. The original, in French, is 1,900 pages.

“The amount of work that goes into turning a 2,000-page book into this small one is quite a lot, and the opportunity for transformation is huge,” she says. “There’s an immense opportunity to prioritize what would be important, legible or interesting to readers. Translation can take many forms, from literal sentence-by-sentence translation to just improvising on a theme.”

As the Crown Junior Chair of Middle East Studies in Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, Johnson researches 19th century Middle Eastern culture, which she says is characterized by economic and social connection between Arabic and European countries.

“In the early 19th century, everyday people — writers, translators — were all, I think, feeling the impact of what we would now call globalization,” Johnson says. “And it is at that moment that the Arabic novel emerges for the first time.”

That emergence, according to Johnson, was driven in part by the translation of European novels into Arabic. And those translations — those interpretations — are at the heart of her work today.

Recording cultural change

“The translation of one text into another is informed by social context, historical events, intellectual movements, et cetera,” she says. “To simply say ‘a European novel arrived in the Middle East,’ discounts the entire process of interpretation that happened. The novel that arrives is not the same thing as the novel that left.”

Johnson says literal translations have historically been seen as the most valued, but there is much, if not more, to learn from looser translations.

“I would argue the least literal translations are the more important works,” she says. “They have the most interpretive content, and sometimes there are multiple versions. ‘The Count of Monte Cristo’ was translated eight times within a 40-year period. And if you look at those eight translations, you can see a historical record of the world in a particular place at a specific moment. And you can see how that particular place is changing over time.”

The less literal, “bad” translations, as Johnson affectionately calls them, “are a source for understanding what the world is.”

Developing a clearer picture of the present

Johnson offers the use of the European word “telephone” as an example. Once the device itself — and knowledge of the device — arrives in the Middle East, there is debate in the Arabic press about what to call it, Johnson says. Should authors simply use the European word? Should they reshape an older Arabic word to make it mean “telephone?” What is that process?

Telephone in formal Arabic is now hatif, but Johnson says most people use telefone or mobile in conversation. This naming of the modern device in the Arabic language, and the enduring use of the English word as well, demonstrate the interconnectedness across countries and cultures.

“The world is not just a thing out there that we can learn about, but is rather a set of connections that we have to put together as a society,” she says. “And the image that results changes over time, and it also changes depending on where you’re living. If you’re living in Beirut in 1865, globalization looks very different to you than a person living in Chicago in 2019.”

Through translation, Johnson says, we are able to see structures of power and geopolitical landscapes over time. We can see how art and politics braid together, and the ways in which our lives today are informed by, and built on, the lessons of previous pages.