Northwestern University engineer John A. Rogers has done something remarkable, steering his innovative "bio-integrated lab" invention to a rare level of cultural prominence as part of an art exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

MoMA’s new exhibition -- “Items: Is Fashion Modern?” -- opened Sunday (Oct. 1) to critical acclaim in New York City, where the exhibit is exploring the past, present and future of 111 garments and accessories that have strongly impacted society and culture over the last century. The curators read about the Rogers invention, were taken by the artistic aspects of his design and invited him to include it.

The exhibition examines the intersection of fashion and functionality, design and technology, and in the case of the bio-integrated lab, the convergence of science and art. It provides a rarified space for Rogers to showcase his first-of-its-kind soft, flexible microfluidic device that easily adheres to the skin and measures the wearer’s sweat to show how his or her body is responding to exercise.

Among fanny packs and flip-flops, a kippah and a keffiyeh -- comes Rogers’ wearable, skin-like microfluidic system that captures minute volumes of sweat and performs precision chemical analysis of key biomarkers, including pH, lactate, chloride and glucose.

The system uses concepts in bio-integrated engineering and microsystems technology to detect electrolytes and complex chemical species released through sweat during exercise, thereby providing insights into physiological health non-invasively, while communicating with digital devices to pass along the information. In the future, it could have even more applications where electronics integrate inside the body, for monitoring of chemistry and even regulating the body’s health.

“The intimate skin interface and sophistication in engineering design in this new wearable, skin-like microfluidic system enables classes of measurement capabilities not possible with the kinds of absorbent pads and sponges currently used in sweat collection and analysis,” said Rogers, the Louis Simpson and Kimberly Querrey Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Biomedical Engineering and Neurological Surgery in the McCormick School of Engineering and Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

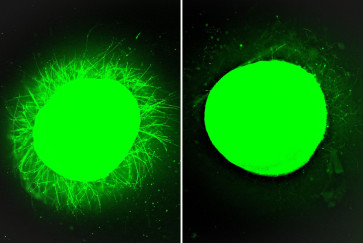

“We use a set of chemical reagents that change in color when exposed to targeted biomarkers, along with arrays of valves and microchannels that route the sweat into a set of associated microreservoirs for analysis.”

A little larger than a quarter and about the same thickness, but in a soft, flexible form like the skin itself, this simple, low-cost device analyzes key biomarkers to allow a person to make adjustments, such as drinking more water or replenishing electrolytes, if medical imbalances arise. Rogers first published the details of his versatile platform last Nov. 23 as the cover story by the journal Science Translational Medicine.In an interview, Rogers moved beyond engineering to offer his personal reaction to the inclusion of his device in the MoMA exhibition, noting, “It’s supercool, that’s the best way I can describe it. It never even entered my consciousness that this would be presented as an opportunity. We’re pretty good at science and engineering, but we never imagined that our work would be recognized for its artistic value, particularly at this level.

“I’m very excited about it,” he added. “As engineers, we work hard to develop new science and advanced technologies with the potential for broad societal value. But for things like skin-integrated diagnostic devices, people experience an unavoidable, natural and very personal connection to the technology -- by paying attention to the artistic parts of the design, you can create excitement around the aesthetics, thereby greatly increasing the rate of adoption. We’re thrilled, and somewhat surprised quite frankly, that our artistic capabilities in this context have passed muster with experts at the very highest levels. This exhibit is a great way to highlight new technologies and where things are going, in terms of the intersection between art and engineering.”

Discussing the factors key to the inclusion of his device in the exhibition, he said, “The fashion aspects are critically important -- people are much less likely to wear something on their skin if it looks like a medical appliance,” he said. “The devices we’re building have these unique physical, engineering challenges in intimate, yet comfortable and non-irritating, integration with the body, but the emotional judgments are just important. As engineers, we have to consider these things.”

This exhibit is a great way to highlight new technologies and where things are going, in terms of the intersection between art and engineering.”

Northwestern engineer

As a specific example, initial attempts in using devices with basic designs on children highlighted an underlying reluctance around the technology, he added. “But you take the same device and put cartoon graphics of a Minion on it (cartoon characters from the film ‘Despicable Me’), suddenly the kids can’t get enough of them. Because of their essential function in health care, you’d like to see these types of devices used in a ubiquitous way.”

The technical challenge was in reformulating computer chip technologies and microfluidic lab analysis systems into thin, soft and skin-like forms to allow natural modes of integration with the body. Rogers’ team has been able to create technologies that blur the interface between technology and biology, to establish “an interface for the skin that is more like a temporary tattoo, rather than a Fitbit.”

He has been exploring “skin-integrated platforms that permit continuous long-term monitoring, but are imperceptible, from a sensory standpoint, even as they provide continuous, clinical quality data and measurements of body processes,” he said.

Rogers added, “You put it on and forget that it’s there. It is almost like a second skin, completely non-irritating and bio compatible.

“And from the standpoint of design, the appearance really matters as well -- people will not wear a device if it doesn’t look good on their skin. The color and geometry; the shape and the form -- it all has to be right.”

Rogers and his team are now using these inexpensive devices with several professional sports teams, doctors and medically oriented organizations like the National Kidney Foundation.

The McCormick School of Engineering has long been a leader in multi-disciplinary innovation, intersectional research and “whole-brain engineering,” and it is partnering increasingly with other fields of study, like art. In fact, Northwestern Engineering collaborates with Northwestern’s Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art to bring artists to campus to expose students to their processes while offering artists opportunities for their work to be nourished by interactions with Northwestern faculty.

Read more about partnerships between engineering and art.

Lisa Corrin, the Ellen Philips Katz Director of the Block, sees the intersection of art and science as similar creative pursuits. It makes perfect sense to her that a renowned art museum like MoMA would introduce the design thinking of Rogers to the general public.

“Art museums are about all kinds of art and all kinds of human creativity, and Northwestern University is on the cutting edge of this.”

Corrin sees the MoMA exhibition and Rogers’ place in it as a very relevant reminder of the importance and impact of science, technology and design on people and culture.

“The role of a museum is to share highly specialized knowledge with the general public,” Corrin said, “and it makes it a concrete part of people’s lives.”