Game theory allows economists to view problems in the social sciences as “games,” or competitions between self-interested parties who understand that their fates are in some way intertwined. Both parties cannot “win” equally, and so begins the game. Jeff Ely, Charles E. and Emma H. Morrison Professor of Economics at Northwestern University, explains Game Theory using the example of fake news on Facebook.

It’s a naïve prescription to say Facebook should put a filter on what it deems to be fake news.”

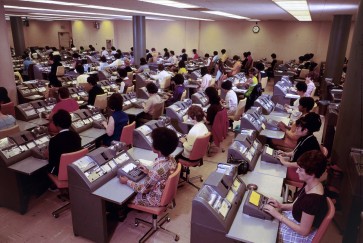

economics professor

Facebook has recently come under fire for echoing what are apparently fake news stories, potentially changing people’s minds and the results of the 2016 presidential election.

“It’s a naïve prescription to say Facebook should put a filter on what it deems to be fake news,” Ely says, laying out the “game” at play in this scenario.

Initially, there are two players: one is the person or group fabricating news stories and the other is the reader who encounters stories and isn’t immediately able to discern whether a story is fake or not. This reader may know about the first player. They may be aware that there is a malicious agent behind the scenes generating some fake news. The reader, therefore, has a dose of skepticism about any piece of information they read.

Enter the third player, Mark Zuckerberg, who decides to filter the news stories that appear on Facebook. This affects the game in two ways:

The reader is now more likely to believe any piece of news that appears in their feed, because the reader is presumably less likely to see fake news. This, Ely says, is the first-order effect of the filter.

The secondary effect is just as important, if not more so. The use of a filter creates what Ely calls a “strategic incentive” for the person or group making fake news. From their point of view, a filtered Facebook is an even more desirable place to spread fake news because readers believe the news even more than they did previously. They are less likely to be discovered as frauds.

Careful analysis is needed to determine whether such a Facebook filter could lead to more or less fake news, or better informed voters, Ely said. Nonetheless, game theory can illuminate the opposing strategic objectives of all the players in the game, which people may not be appreciating when they decide whether filtering news is a good idea. “It’s not so obvious,” Ely says.

Read more about Ely’s musings, economic and otherwise, at CheapTalk.org, a blog he co-produces with Sandeep Baliga, professor of Managerial Economics and Decision Sciences at Northwestern.