EVANSTON, Ill. --- Marcellous Lovelace’s street savvy works are based on his experience growing up and living in poverty on Chicago’s far South Side. Almost completely self-taught, he refers to himself as an “Afro urban indigenous folk artist.”

More than 30 of Lovelace’s works of all sizes and mediums will be featured in his solo show, “#Biko70 Lumumba Blacker than Space,” Feb. 15 through March 20, at Northwestern’s Dittmar Memorial Gallery. The exhibition is intended to convey the story of people who are overlooked inside a segregated, biased space overcome by poverty, crime, food deserts, joblessness, gang violence and police brutality.

The exhibition, an opening reception from 4:30 to 6:30 p.m. Friday, Feb. 19; and an artist lecture, from 4:30 to 6:30 p.m. Thursday, March 3, are all free and open to the public. More information available online.

The gallery is located on the first floor of Norris University Center, 1999 Campus Drive, on Northwestern’s Evanston campus. Hours and locations available online.

Lovelace began to draw and paint between the ages of 6 and 8. By age 11 he had become more knowledgeable about African culture in art. Since 1996 he has created at least one painting or drawing a day.

The segregated, poverty stricken environment in which Lovelace was raised has helped him to develop more than 400 images a year during the past two decades.

As a child, he was inspired by the graphic art of Emory Douglas, who was the minister of culture for the Black Panther Party from the late 1960s until it disbanded in the early 1980s, as well as AfriCOBRA art (a collective of Chicago African American visual artists).

He also was influenced by his favorite television cartoons, including “The Jackson 5ive,” “Fat Albert and the Gang,” “Harlem Globetrotters” and “Mr. T.” Now his main inspiration comes from African-American artists Hale Woodruff, John T. Biggers, Horace Pippin, William Johnson and Charles Wilbert White.

Lovelace’s works often incorporate recycled materials that he collects throughout Chicago and Illinois, as a reference to his surroundings. These found items include pieces of paper, magazines, garbage cans, old tires, discarded mattresses and construction materials from demolished buildings.

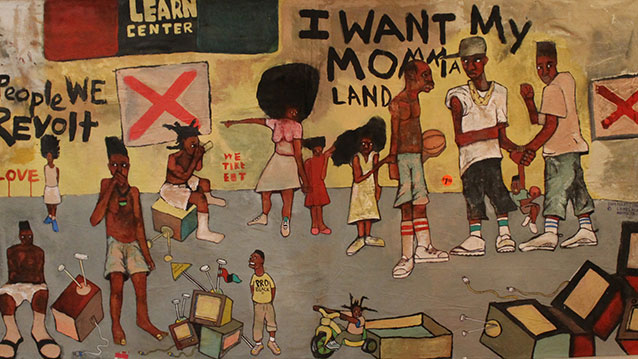

Lovelace’s favorite subject is the human form. His mixed-media paintings range from neighborhood street scenes that depict groups of black teenage boys -- some brandishing a handgun or clutching a basketball -- to muscular action heroes and voluptuous female figures. Some of the street scenes have a backdrop of graffiti-covered buildings or storefronts.

One of the highlights of his Dittmar Gallery exhibition is “We Accept EBT and Guns.” The focal point of the painting is a young black man in a baseball cap holding a handgun in the palms of his outstretched hands -- and offering it to the viewer. He is surrounded by what appears to be three supportive friends. To the right is a sign alerting passersby that whoever is collecting handguns also is accepting EBT (electronic benefit transfers), which have replaced paper food stamps and checks in impoverished Chicago area communities.

Lovelace’s mixed media paintings are done in spray, acrylic and Latex paint, enamel and many other water-soluble mediums. He also has used house paint, shoe polish, Georgia red dirt and ordinary ink pens.

Lovelace attended the School of the Art Institute for one year, but left due to financial hardship. While he was there he took painting classes based on collage, material usage, large-scale painting and decomposing images, in addition to writing and screen-printing classes.

“That was a great opportunity for me to learn, and I wish I could go back and teach there one day or do an art show or both,” he said.

He also took painting classes and worked with a mural artist in San Francisco and studied in Memphis, where he was told that “Black Art was not art.”

“I did not let that (comment) distort me as an artist; it made me want to paint more,” Lovelace said. “My environment is so negative it helps me to create beauty from this struggle. I paint because it’s the only thing that feels good after feeling like I’m trapped in a world that has no hope.”

Lovelace’s work has been exhibited locally, nationally and in Italy and Germany. More information on the artist is available online.

When he isn’t creating visual art, Lovelace creates hip-hop music, something he has done since age 12. His music has taken him around the world. As a hip-hop artist/creator, he records an average of nine to 14 albums a year, and mainly performs in foreign countries as an independent underground musician. Information on his music is available online.