EVANSTON, Ill. --- Jerry Truong’s “School Works” exhibition examines the political implications of the American educational system through large-scale blackboard-like paintings and sculptures that utilize objects typically found in a grade school classroom.

These objects range from plastic chairs and overhead projectors to signs that display summaries of notable teaching philosophies, items the artist sometimes finds through Craigslist or surplus and thrift stores.

Truong’s Fall 2015 exhibit is making a five-week stop at Northwestern’s Dittmar Memorial Gallery from Oct. 29 through Dec. 6. The gallery is located on the first floor of Norris University Center, 1999 Campus Drive, on Northwestern’s Evanston campus.

The exhibition and an opening reception from 4 to 6 p.m. Thursday, Oct. 29, are free and open to the public.

Truong, based in Silver Spring, Maryland, teaches at a community college in Prince George’s Country, Md. In the classroom, he began reflecting on his role as an educator and the values he wanted to instill in his students.

The result was his latest body of work. “‘School Works’ strives to embody all we hope for out of school,” he said. “It is a space that encourages learning and independence, but also the very thing that we fear it could become: A site of conflict as a political tool.”

His critique points out the contradictions embedded in education, while simultaneously referencing philosophical, social and political ideas and art movements that challenge traditional modes of thinking.

Exhibition highlights include three pieces with dual titles that serve two purposes.

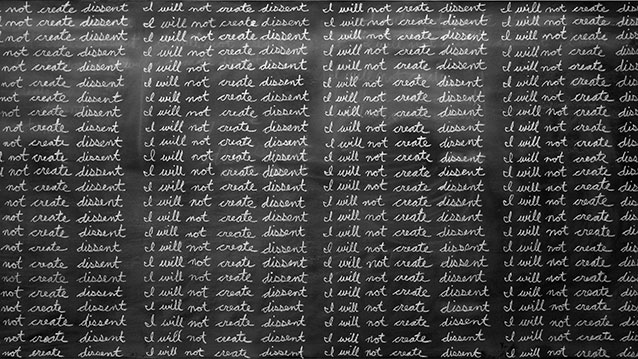

- “Conflict Management or How to Not Be Unpatriotic” not only is a painting, it also functions as a record of performance. The piece features the repeated phrase: “I will not create dissent,” neatly written by hand, over and over again, in chalk on a blackboard panel. Truong said he personally wrote the words over several hours, as a form of self-punishment.

“School is a place where one is supposed to learn to be a freethinker and challenge convention, but it is also a place where people are afraid of disagreement and intellectual conflict,” the artist explained.

- “Rise Up From Every Corner or Maybe I am a Monumental Failure” is a sculptural installation tended to evoke two images: the iconic dunce and Tatlin’s tower. (A child punished for being a slow learner, sitting in the corner with a tall, pointed hat on his head and a tower designed by Soviet artist and architect Vladmir Tatlin that was intended to be built in St. Petersburg several years after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, but never was. The tower’s complicated vertical and spiral metal and glass design has inspired generations of artists.)

After researching writings and interviews related to artists and writers who made teaching central to their various creative practices, Truong created a series of these signs as a distillation of each important, creative figure’s philosophy about teaching.

- “To The Cryptics and Cynics, a Modest Proposal For a New Kind of Revolution” is one of several different vinyl on polyester film signs. Eight of the signs are done in white vinyl, which are difficult to see, and six others are in black vinyl, for more contrast.

Truong hopes that visitors will take the time to explore and interact with some of the pieces in his show.

“Look at the artwork labels, ponder the dual titles, and eventually you will arrive at your own conclusions after some reflection,” advised the artist.

Truong is a first-generation American who was raised in Northern California by parents who emigrated from Vietnam. He admits he was coddled by the suburban American dream, oblivious to the social and political mechanisms that made the family’s way of life possible.

“Even in my own home, I was blissfully unaware of the sacrifices my parents made to arrive in this land,” he said. “They never once spoke of the horrors they survived when they escaped in 1979 from war-torn Vietnam by boat; the constant fear of pirates, suffering from starvation, and witnessing family members drown.”