This article originally appeared in the Chicago Tribune on May 10, 2013.

By Christopher Borrelli

Zach Braff (Northwestern University, class of '97), the third most popular Zach in Hollywood (after Galifianakis and Efron), went back to his old school last week. He'd returned to teach an acting class, a one-time workshop. The day before, he tweeted: “Illinois, I am in you.” Then later, more nostalgically: “Northwestern University, I'm back. Are we good at sports now?” I had assumed Braff was not a big deal anymore — that, though “Scrubs” reruns remain a fact of life and memories of “Garden State” linger, his voice acting (“Oz The Great and Powerful”) and Kickstarter campaign to raise money for a “Garden State” follow-up spoke volumes.

And yet, that campaign has raised $2.5million (and counting), and the lobby outside the classroom, the Mussetter-Struble Theater on the Evanston campus, was an undergraduate mob scene.

So I waded in. Besides, every year about this time famous people offer vague and sunny advice to college students, and Braff, speaking to a small, more specific pool of hopefuls, might get real, practical.

I was right.

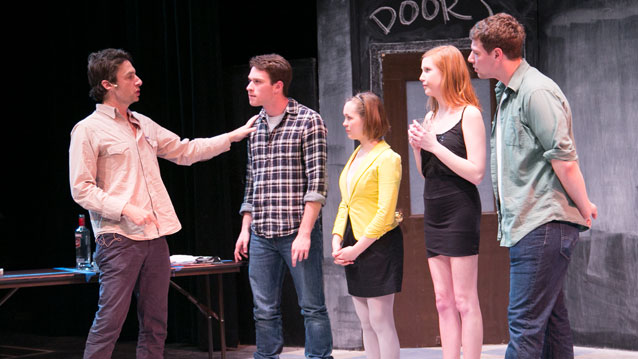

Braff sat in the front row of the theater, beside David Downs, associate professor emeritus in Northwestern's theater department (and one of Braff's former teachers), and Mary Poole, longtime Northwestern senior lecturer in theater. As seats in the small house filled with students cradling notebooks and chewing pens, a handful of junior and senior theater majors huddled in the wings, between the curtains, waiting to go on. The plan was: They would split into three teams and work through scenes from “All New People,” Braff's first play, which debuted off-Broadway in 2011. Then Braff would tell them what they did wrong or right. (Just before the students went on, Poole gave a joshing pep talk: Remember, none of you will get a job out of this, so just have fun.)

When class began, Downs stood and explained that Braff was here at the invitation of the School of Communication, part of an endowed guest-lecturer program. Then Braff stood and said Downs was “the best teacher I have ever had, much like Robin Williams in ‘Dead Poets Society,' opening those kids' eyes up …”

He sat.

The scene, Downs said.

Oh, right, Braff remembered, jumping up. “When the curtain opens,” Braff explained, “the lead character (Charlie) is standing on a chair, a noose made out of an extension cord hangs from the ceiling. Charlie is about to kill himself, he is about to step off the chair and end his life, and all of a sudden …”

Eyebrows raised, scene set, Braff lowered into his chair, rigidly upright, as if impersonating a hunting dog.

Two students walked out, and the scene began.

Charlie stands on a chair, noose before him, leaning back to light a cigarette, when the door bursts open. Enter Emma, a manic Brit. She screams, Charlie chokes. What are you doing here? he wants to know. She asks the same. We learn they are in an island beach house, which she is showing to prospective renters. She is a frantic Diane Keaton type, stoned, talking a mile a minute. Also, we learn Charlie killed six people.

And end scene …

Braff sprung up:

“That was awesome! You both have the ultimate high-class problem: You're not pausing for laughs, so we can't hear the next sentences. You're doing it so good, you have to slow down. … But it's tricky because every single audience is different, and we did this show in New York, in London, and when you do a show, those 600 or 700 people will never be in the same room together again. You know what the big laughs are, and the audience will roughly follow the same path, but you'll have a joke that will kill one night and the next, there will be a titter and you won't have any idea what happened!

“But this opening sequence is very hard because it's setting up the whole tone of the play, which is, yes, you're going to laugh, but it's ultimately going to be a balance of zaniness and tragedy, some very deep things. And Charlie has the onus of keeping this dark tone alive, but also, keep in mind that Emma is very stoned. And I don't endorse that behavior but I did a little research while I was at Northwestern. What the audience will learn is she is on the verge of being deported and doesn't want to go back to England, and that's why she is manic and crazy. But play her lightly, the audience doesn't like her. That's one of the things we figured out: She's funny but, (expletive), this guy's on the verge of killing himself!”

He sat down.

The students nodded and walked off. A new Charlie and Emma, more nervous than the first, walked out.

Charlie urges Emma to leave. The doorbell rings. It's Myron, a firefighter, who is bringing drugs to Emma. We learn Charlie lied to Emma: This is not his house! It is the house of his stockbroker friend. Myron does not trust Charlie, who, having established that he has murdered, threatens to kill them if they don't leave.

And end scene …

Braff is less enthusiastic. He climbs slowly out of his chair:

“Really good guys, but if we can go back and take some notes, you can try again. … We learn later that (Charlie) is totally infatuated with (Emma) and in love with her, so there is a total chess match between Charlie and Myron! (To the student playing Myron:) I thought you were a little too comfortable too quickly, and he's more of a cocky bastard and sort of sizing this Charlie guy up. … Also, you guys are doing the same thing, you're not waiting for laughs, you're going on to your next line. Then again, if you let it get too light. … Who likes ‘30 Rock'? ‘30 Rock' was hilarious. I think it's hilarious. What ‘30 Rock' chose to do was stay way up on the farce, so they didn't have the choice to be dramatic. As much as I love the show, I think one of the reasons it never had the audience was because it never made the audience feel (the characters) were real. They were these amazing characters, but they were these farcical characters, so — yes, Mary …”

Poole lowered her hand: “Can I say that I think that ‘Scrubs' actually did both?”

Light applause.

“Thank you, Mary,” Braff said, head lowered. “I can take that compliment because I didn't write that show. One thing Bill Lawrence, who created the show, was a genius at doing was that: You could be as crazy as you wanted, but it was grounded in reality. The American Medical Association said it was the most accurate medical show! So when it dropped into reality, it was 100 percent straight. Which meant you earned your crazier moments. Which is some of what I was trying to do in this play: You can have a fireman drug dealer if you don't lose the grounded nature of ‘Holy (expletive), there's a suicidal, homicidal murderer in the room!'”

The students returned to their marks and began again. The student playing Charlie said to Myron: “Are you a firefighter?” And the student playing Myron replied, brusquely: “I'm a gay stripper. What's with the noose?”

Braff jumped off his seat: “OK, the laugh there should have come on ‘gay stripper'! Which I think is funny …”

The student shrugged.

“Well,” Braff said, “I promise you, big laugh there.” Throughout the class, he spoke this way, quickly, earnestly, with self-deprecation; he received C's at Northwestern in screenwriting and acting, he said, apologizing that “All New People” — sitcom-y, unfocused, with nuggets of fun -- was “all over the place.”

New students stepped in.

There's another doorbell ring. This time, it's a beautiful blonde. We learn she is a prostitute with a heart of gold and that Charlie's stockbroker friend sent her to Charlie, to cheer him up. Myron asks how much she costs. She costs $15,000 a night, which sends Myron into an extended speech about Wall Street fat cats.

And end scene …

Braff's expression went from a cringe to a quick smile. He walked onto the stage

“Great, great job. Couple of notes: You guys are moving on punch lines. Which is something I learned (not to do) from David. You will instantly dissipate a punch line if you are walking while saying it. I don't knowwhy it is so but it is so. (Turning to the new Myron:) I hate to say, but you're playing the jokes a little too much. The lines are there. You're a funny actor but you're winking at the audience. … I can be as hammy as anybody, but when the line is there you have to trust it. And that monologue about stockbrokers, that's real! The real Myron drops in! He's a blue-collar guy, it's something that infuriates him — his taxes bailed out Wall Street! Mary, how much time?”

“Fifteen minutes.”

“For the whole thing? (Expletive)! I want to end on words of wisdom!”

And so he did.

He walked to the side of the stage and located an image of his iTunes artist page that the school had enlarged for him. He held the cardboard in front of him and he read the reviews: The first review was a one-star review (“garbage”), the second review was a five (“wonderful”), the third was a one (“I wanted to jump off a cliff”), the fourth was a five (“classic”). Braff waited for the laugher to die down, then he said, more coherently than anything in his play: “I am a little used to this by now. I read a comments section and it says I should be deported. Then someone writes that they proposed to their girlfriend after seeing ‘Garden State.' That's fine. There are people who will hate what you do and people who will love what you do. You're going to be in plays and you're going to be in movies, you're going to have reviewers say you're a genius and you're going to have reviewers say you should quit. But now more than ever, you have to be yourself and be fearless and not be stopped from being your true selves by the ones and threes of the world. Thank you.”

And end scene.