- Inexpensive test has 95 percent accuracy rate

- First evaluation to begin soon in Mozambique

- Nonprofit biotech company is new business model

- University played active role in setting up foundation

EVANSTON, Ill. --- Today, mothers in Africa sometimes walk more than 10 miles to a clinic only to learn that conventional HIV test results for their babies are not available yet. Many never come back or even get their infants tested in the first place.

Soon residents in Maputo, Mozambique, will participate in the first evaluation of an HIV test that was developed at Northwestern University and differs dramatically from conventional tests that are complex and slow to produce results.

The first-of-a-kind test will deliver a diagnosis in less than an hour while mother and child are still in the clinic -- and, if all goes well, could dramatically improve the rates in which infected infants are diagnosed and treated.

“Our test provides while-you-wait results, and if a child is infected, he or she will begin treatment immediately, which is critical to survival,” said David Kelso, who led the development of the technology in his Northwestern lab.

Kelso is a clinical professor of biomedical engineering at the McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science. He also is director of McCormick’s Center for Innovation in Global Health Technologies.

The test is a miniaturized, inexpensive version of the p24 HIV test and is designed specifically for use in developing countries.

"One and a half million infants in Africa and Asia are born to HIV-positive mothers each year, but only a fraction of the HIV-positive infants are identified in time to start treatment. While adults can manage the disease for decades, an infant who isn't treated likely will die within a year or two."

Kelso and his research team developed the technology with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and, in 2010, he and his partners established the Northwestern Global Health Foundation with the mission of developing health solutions for infectious diseases in the developing world. The University played a very active role in crafting a model for the foundation, enabling it to produce affordable HIV diagnostics.

The foundation’s first product is the HIV test and its first client is an international global health foundation. Mozambique is the first of 10 countries in which the health foundation will facilitate, in partnership with local governments, an evaluation of the test.

“The Northwestern Global Health Foundation is a new sort of business: a nonprofit biotech company that helps manufacture and deliver health care products that wouldn’t turn enough profit to be attractive to traditional companies,” Kelso said. “If the foundation works, I think it’s an entirely new way to do business.”

Making sure the technology that comes out of the lab actually makes it to the market is the goal, said Kara Palamountain, president of the foundation and executive director of the Global Health Initiative at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management.

Palamountain and Swati Satish, who received her master’s degree in biomedical engineering from Northwestern in June, were recently in Mozambique training clinicians on how to the use the p24 test.

For Palamountain, visiting rural clinics where nurses see hundreds of patients a day for little money is motivation enough. “For me it’s a responsibility to make sure that others have access to health care,” she said. “The disparity between the haves and the have-nots really makes me want to do something about it.”

The new diagnostic first will be independently evaluated in five clinics across the Mozambican capital, testing infants born to HIV-positive mothers. If this first phase in the Maputo clinics goes well, a second evaluation will be conducted in more rural clinics in Mozambique.

“We won’t be successful until we show this test helps save the lives of infants,” Kelso said of the long journey delivering the foundation’s first product, “but we are getting very close.”

The easy-to-use test has a 95 percent accuracy rate in identifying those infected with the virus. It detects very low levels of core protein 24, made by the virus itself. The conventional diagnostic option is a dried blood spot that is sent to a distant laboratory for testing. Results can take up to three months, long after parent and child have left the clinic, maybe never to return.

Results of the evaluation are expected sometime next year. The study will include a comparison of the p24 HIV test with the current blood spot test and an analysis of how availability of the p24 test affects the number of infants tested and, for those infected, the number who receive treatment.

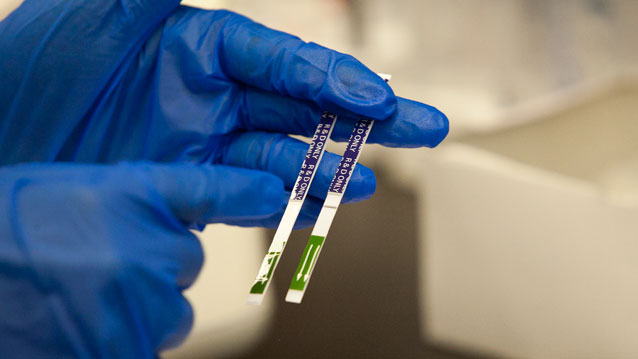

To administer the p24 test, a doctor or nurse takes a drop of an infant’s blood from the heel, places it on a plastic blood-separation membrane, inserts it into a small processor about the size of an alarm clock, and receives results within 30 minutes. The clinician will see two thin black lines on the test strip if the virus is present.

After the study in Mozambique, the health foundation plans to facilitate similar studies in nine more countries. Each country will decide for itself if it wants to use the test in its clinics after receiving the evaluation.

Once the test has proven effective, the foundation will begin selling the inexpensive test in the marketplace, filling a niche. The current cost is $15 per test but that will reduce by half as volume goes up.

Any profits the Northwestern Global Health Foundation earns will be poured back into research and low-cost manufacturing. Kelso and Palamountain hope the successful launch of the p24 test will give them credibility in the African market and allow them to move forward with other tests being developed by the foundation, including viral load and tuberculosis tests.

The foundation also plans to establish a distribution company in Africa that will manage the supply chain for the various tests and train clinicians in their use.

Kelso and Palamountain established the foundation with four other Northwestern University colleagues: Daniel Diermeier, the IBM Professor of Regulation and Competitive Practice at Kellogg; Alicia Loffler, associate vice president and executive director of the Innovation and New Ventures Office; Matthew Glucksberg, professor of biomedical engineering at McCormick; and Robert L. Murphy, M.D., the John Philip Phair Professor of Infectious Diseases at the Feinberg School of Medicine, director of the Center for Global Health and a physician at Northwestern Memorial Hospital.

Kelso’s research and the spinoff foundation directly connect to Northwestern’s own strategic plan goals of actively engaging with the world and discovering creative solutions to problems that will improve lives, communities and the world.

“This is the first time, as far as we are aware, that a university has played such an active role in supporting the development of products that will improve the health in the developing world,” Loffler said.

“To develop the infant HIV test, a new model of innovation had to be created by bringing together donors, corporate partners, University researchers and engineering and business students,” Diermeier said. “This triangular model creates a self-sustaining revenue stream for social impact innovation.”

When the foundation was established, the University and the foundation leadership formed a committee to address how they could best make the foundation work. It was important to engage a commercial partner -- Quidel Corporation -- with similar values to help develop the product and advance the foundation’s global health mission, Loffler said.

The Northwestern Global Health Foundation is a nonprofit organization that is legally separate from Northwestern University. The foundation has licensed technology from Northwestern, and Quidel manufactures the test strip portion of the p24 test and oversees manufacture of the other parts of the test.