Successful glioblastoma treatment in dogs may also be viable in humans

Some dogs’ tumors shrank, one disappeared altogether

Could a brain cancer treatment for man’s best friend also be viable in humans? A promising new study in canines from Northwestern Medicine, Texas A&M University and ImmunoGenesis is giving scientists some hope.

The team of researchers discovered a treatment for canine glioblastoma — the second-most common type of brain cancer in dogs — that reduced the volume of some dogs’ tumors. The findings have promising implications for the human version of the aggressive brain cancer.

In a Phase I clinical trial conducted at the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVMBS) Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, investigators injected an immunotherapy drug known as a STING (STimulator of INterferon Genes) agonist directly into the glioblastoma of five dogs.

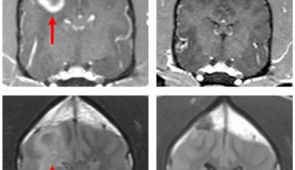

STING agonists can induce immunological responses that allow the immune system to fight otherwise immunologically resistant cancer cells. MRI scans taken of the canines over the course of the trial revealed that some of the dogs, even with a single dose, responded to the treatment with apparent reductions in their tumor volume, including one complete radiographic response, meaning the tumor completely disappeared. The findings lead the team to conclude this therapy can trigger a robust, innate anti-tumor immune response and may be highly effective on recalcitrant tumors such as glioblastoma in humans.

The study was published Aug. 25 in Clinical Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

The immunotherapy drug was developed by Dr. Michael A. Curran, an immunologist and founder of ImmunoGenesis, and is based on ongoing research that included Dr. Amy B. Heimberger, scientific director of the Malnati Brain Tumor Institute of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

Decisions about whether to advance a therapeutic candidate to human clinical trials is typically based on mouse data, Heimberger said. However, these tumors in mice are tiny and there are additional discrepancies in the genetics and immune background between mouse and man brain tumors.

“This is likely one of several reasons why promising preclinical data may not have the same impact during clinical trials,” Heimberger said. “Because canine glioblastoma shares very close similarities to the human counterpoint, we tested this novel immune therapeutic to help us make a go/no-go decision for human clinical trials.”

Both canine and human gliomas tend to have a poor prognosis, as they are difficult to surgically remove, and traditional therapies come with multiple side effects and are expensive. Even after a surgery to remove the tumor and radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy, humans with glioblastoma may only survive a few more months.

Because of the simple delivery of the STING agonist and the marked volume reduction of the tumor, the researchers believe this strategy may provide a viable adjunct therapeutic approach for human glioma.

The trial was conducted at the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVMBS) Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital by Dr. Beth Boudreau, an assistant professor of neurology.

“With this therapy, we were trying to take tumors that do not, on their own, generate a lot of immune response and turn them into tumors that do by injecting them with this immunotherapy agent,” Boudreau said.

In the canine clinical trial, the maximum tolerated dose was limited by the large unresected masses. Heimberger indicated that in human subjects, the standard of care is surgical resection before starting any therapy, and therefore higher doses of the STING agonist in human subjects would likely be needed.

This clinical trial was based on earlier research by the team—including Dr. Jonathan Levine, a neurology professor and head of the CVMBS Small Animal Clinical Sciences Department—which analyzed a massive canine genomic dataset collected from multiple glioma samples. They found that canine and human gliomas are molecularly similar, suggesting that the two diseases have a similar mutational, cancer-causing process that would enable similar treatment strategies.

In the next phase of the project, Heimberger and Curran are exploring using a similar approach in clinical trials of human glioma patients who have undergone a surgical debulking.

Funding for the study, “Intratumoral Delivery of STING Agonist Results in Clinical Responses in Canine Glioblastoma,” was provided by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01 NS120547), the Joan Traver Walsh Family Foundation, the Dr. Marnie Rose Foundation, the Brockman Foundation and Mr. Herb Simmons.

Multimedia Downloads

Glioblastoma tumor in dog